The Menil Drawing Institute occupies a unique niche in Houston’s visual arts scene. Its explicit role revolves around promoting drawing and illustration as media worth displaying and studying in and of themselves, not precursors to the paintings or sculptures more associated with the gallery world. Founded in 2008, the institute eventually moved into a separate building on the Menil campus in 2018, adjacent from the Cy Twombly Gallery, appropriately enough.

As is custom, the gallery featured wide stretches of bone white walls suitable for displaying priceless works. However, the institute’s staff also saw in these blank swaths a potential canvas. They devised of the Menil Wall Drawing Series, a rotating exhibition that invites artists to use one of the largest walls inside the space as an outlet for their own creative visions. Six artists have participated in the series so far: Roni Horn, Jorinde Voigt, Marcia Kure, Mel Bochner, Marc Bauer, and Ronny Quevedo, whose triptych mural C A R A A C A R A is currently on display until August 31.

The artists selected to take part in the series bring to the space such a unique spectrum of ideas and aesthetic sensibilities, it illustrates (pun intended) the infinite potential of a seemingly simple wall. Horn and Bochner went a more minimalist route. The former wrote a collection of clichéd phrases, while the latter left behind a scraping of blue carpenter’s chalk, titled Smudge. Voigt, Kure, Bauer, and Quevedo opted to fill all of the 36 feet made available to them with vibrant mélanges of color and line and movement. Bauer even returned to Houston from his Zurich home to add, subtract, and edit figures in his RESILIENCE, Drawing the Line as he got to learn more about the Bayou City’s queer communities and constant uphill battle against climate change.

“We do a number of studio visits every year to introduce ourselves and our program to who we think are artists working with drawing today that are working with it in really interesting ways… We really think about who will add a new perspective, add a new theme, add a new viewpoint to what’s come before,” Montana says. “We’re still in a phase of the program where we are really looking for someone to stretch the boundaries of what this program can be and really stretch the boundaries of what our audiences have seen before in this series.”

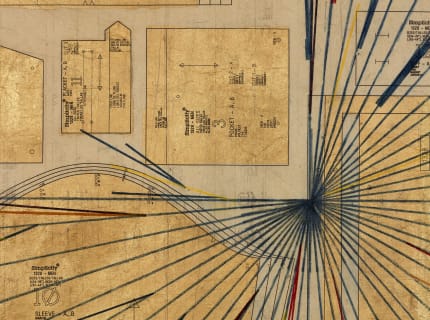

C A R A A C A R A undeniably fits this criteria. Quevedo’s contribution divides the space into three panels, each layered with overlapping cosmological charts, clothing patterns, and sports plays (mainly soccer and basketball). His mother was a seamstress, and his father was a professional athlete; the artist begins with these personal touchpoints to offer viewers ruminations on geographic and creative connections between North and South American peoples, material culture, and the self—all united under one starry sky.

“I’ve never worked at this scale. The idea was to take a technique or process I’m used to and scaling it up. I think [C A R A A C A R A] was very much a response to the site. I would say as soon as the invitation to commit to it started, that’s when the work conceptually started happening,” Quevedo says. “The physical aspects of it probably took a week to make the thing happen on site. But the concept and the ideas probably took over the course of the year.”

Each section of the triptych is distinguished from one another through the use of a dark blue wax transfer paper, which Quevedo’s mother would use in her sewing work. They run through a gradient from light patches to near opaque coverage. Depending on which part of the work one looks at, the wax either highlights or obscures the lines and patterns the artist carefully gouged into the wall using a CNC router machine.

“I’m really interested in how we map things in a topographical way, how we often kind of feel that topography can provide a container for a really abstract or really expansive space. I feel like conceptually, there’s something about our attempt to want to understand those things as a kind of search, either for self or a search for meaning,” Quevedo says. “For me, it’s personal, but also something that is shared by people. While we may not understand how a pattern can help you create a dress or a jacket, we understand what it’s like to step into that. We can understand how mapping has helped us create a sense of space, a sense of the world.”

...

Read full article at houstoniamag.com.