Whenever I’ve been lucky enough to see Ruby Sky Stiler’s work in person, I’ve come away thinking about the idea of the material metaphor. By this I mean something like the collapse of subject and content into form and expression; a mode in which the meaning of a work inheres in the material itself and how it is used by the artist, as opposed to one in which material is subservient to expression. In her 1982 lecture Material as Metaphor, Anni Albers said: “What I am trying to get across is that material is a means of communication. That listening to it, not dominating it, makes us truly active, that is: to be active, be passive. The finer tuned we are to it, the closer we come to art.”1

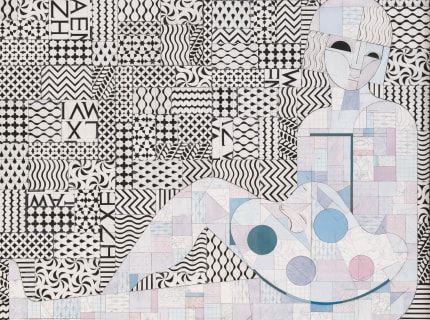

In New Patterns, an exhibition of new and recent works by Stiler currently on view at the Tang Teaching Museum in Saratoga Springs, New York, the material metaphor finds a particularly poetic and resonant expression. This elegantly spare presentation includes eight human-scaled works on panel that render various portrait types—reclining nude, parent and child, self-portrait as artist—in intricate mosaics of pastel-hued shapes against patterned backgrounds, the subjects’ faces and bodies mostly abstracted or idealized. These works are installed within a mural encircling all four walls of the gallery with a continuous sculptural line that traces the contours and outlines of five archetypal female figures, some standing at least ten or fifteen feet tall. A final element further turns the space into a singular installation: a functional site-specific bench, titled Bathers (2021), whose undulating blue waves call to mind a frequent motif in Impressionist and modernist depictions of the female nude, while also granting visitors a comfortable vantage from which to contemplate the rest of Stiler’s work.

When viewed up close, however, the magisterial portraits included here dissolve into seemingly infinite plays of surface, image, and material. The media listed for the works on panel include acrylic paint, acrylic resin, paper, glue, and graphite, but Stiler’s treatment—building up thickly-encrusted layers and incising them to create deep relief—turns these humble materials into surfaces that resemble marble, terracotta, or tile in some places, finely carved wood in others. Some of the paper elements within the portrait figures contain graphite drawings of swirling botanicals, birds, and geometric patterns; others carry numbers, alphabets, and inscrutable passages of text, sealed behind washes of translucent paint. Certain body parts, like hair, fingers, toes, and one particularly memorable penis, are carved from extra thick layers of paint and resin. As such they seem to leave the two-dimensional plane and bring Stiler’s figures to life. The backgrounds behind them dissolve into exquisitely contrasted and criss-crossed black-and-white patterns, whose handmade imperfection is accentuated by visible graphite drafting lines.

...