Kang Seung Lee, who was born in Korea and is currently based in LA, illuminates the transnational queer history and the lives of minorities through his art. Like the makeup of a constellation, the dual exhibitions of video and installation work in the Arsenale and Giardini are an attempt to connect the dots of the queer lives he has discovered until now. As he said, “When more than two stories or images are brought together, a new meaning is always born.” This is the birth of a new story.

Harper's Bazaar: At the 60th Venice Biennale, your video work Lazarus and a new installation Constellation are presented. I would like to start with the new artwork at Giardini. By investing years of research into each project, you have been able to connect a particular individual’s life and works with historical events. Does Constellation follow this pattern as well?

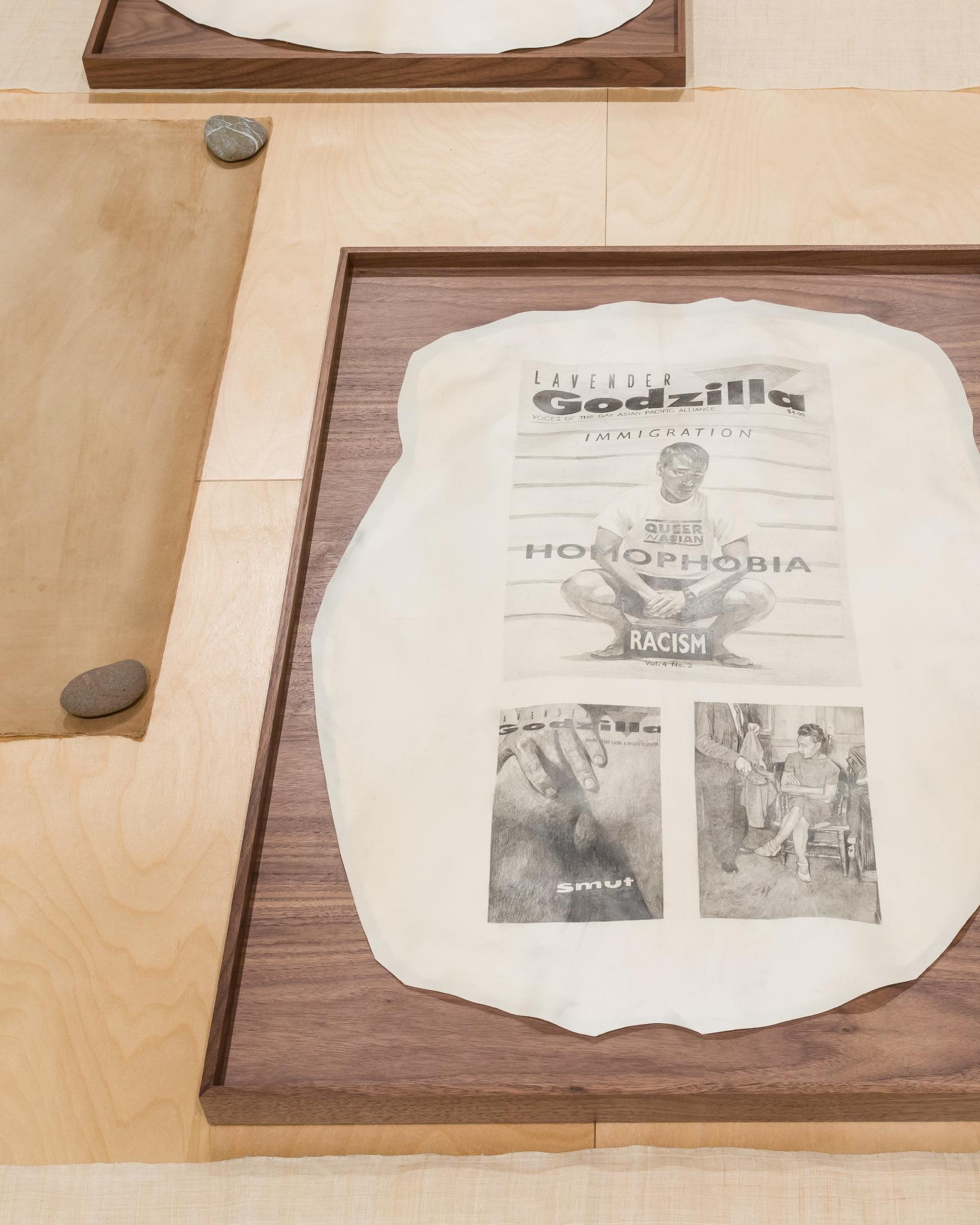

Kang Seung Lee: As the title suggests, these are stories resembling constellations. All the people from various projects since 2016 appear in this work. Works on transnational queer history and the lives of minorities are presented together, paying attention to the meaning that was born when they were lined up together. As for Untitled (Constellation), it is a series of more than 60 small works. Under the stem of queer history, diverse media works were arranged on countless closely connected people, especially related to traumatic events such as the AIDS epidemic. There is no specific timeline laid out. Each task does not follow linear time, but pops up or overlaps each other. I believe that when more than two stories or images are brought together, a new meaning is always born.

Harper's Bazaar: As mentioned, Constellation is a large installation series of smaller works. You are excellent at controlling the tension between the audience and your work by increasing or decreasing its scale. I am curious to know what ‘size’ means to you and how it is reflected in this exhibition.

Kang Seung Lee: The Scale of the work determines the relationship between the image and the viewer. Constellation is recognized as a complete work, but it also contains details that can only be perceived through very careful examination. In order to properly understand the work, the audience must get very close to it. This exact relationship resembles an effort to examine the history of minorities from a microscopic perspective, recognizing mainstream history.

Haper's Bazaar: You used seeds and plants from Port Road Beach in Singapore and Elysian Park in the United States as materials. What is the significance of these places when it comes to queer history?

Kang Seung Lee: Elysian Park and Port Road Beach are famous cruising spots. Homosexual activities were considered illegal in Singapore until 2021. Although it died out in the 2000s, up through the 1990s, there were frequent sting operations on Port Road Beach, in which undercover police pretended to be gay and consequently made arrests. Singapore’s main daily newspaper, The Straits Times, used to publish detailed stories about these arrests, exposing real names. Singapore is a small country and it is easy to recognize people around town. However, most of these official records have disappeared, along with similar minority histories around the world. One might say that an attempt to write a minority history has failed. That said, objects such as seeds and plants derived from these places are longstanding, metaphorical evidence of such forgotten minority history. The very plant I brought back is not the same plant that was growing there at the time, but it is not different either. I think this attempt itself is a rewriting of history–a retelling from a contemporary point of view. History has always been rewritten and modified in this way.

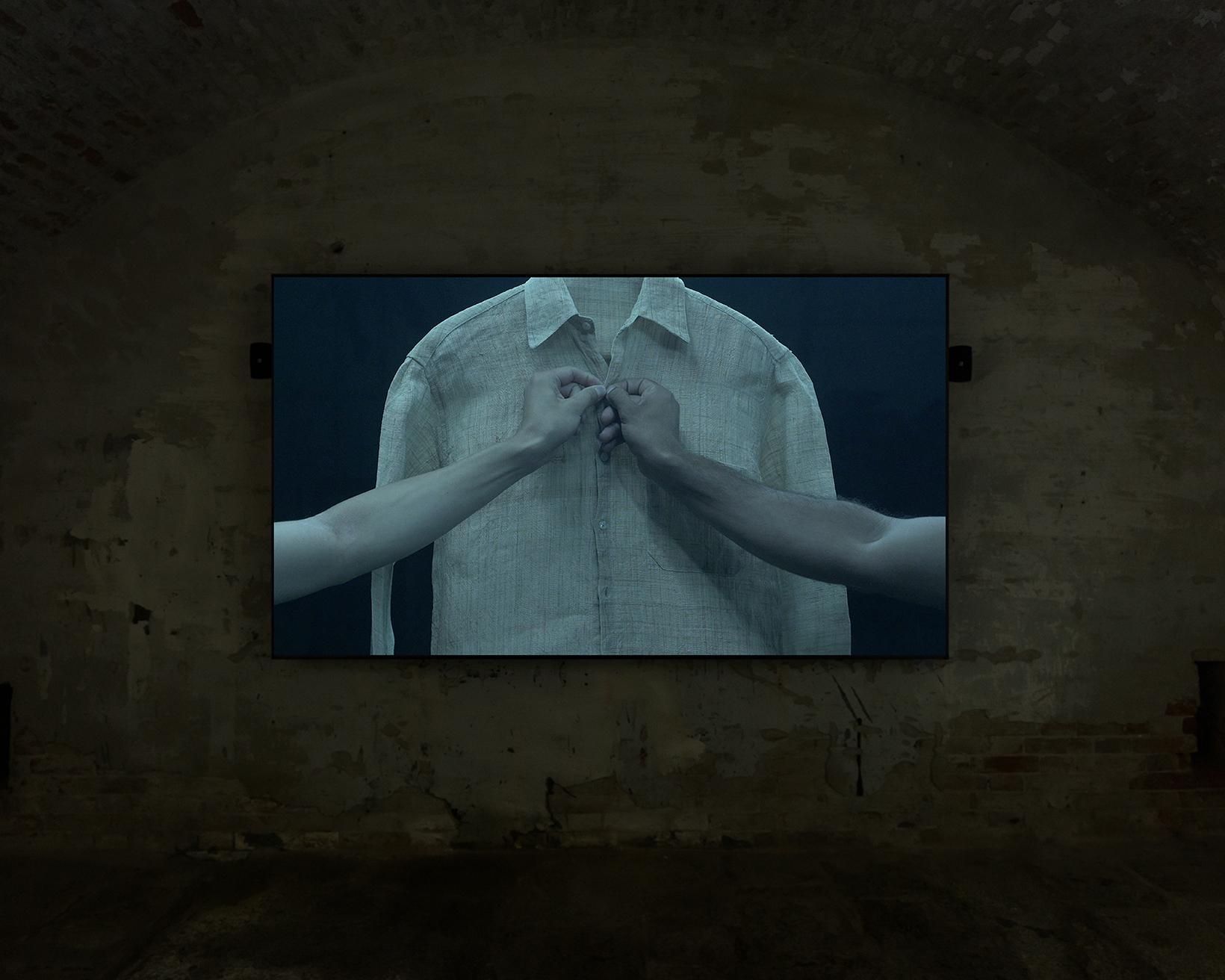

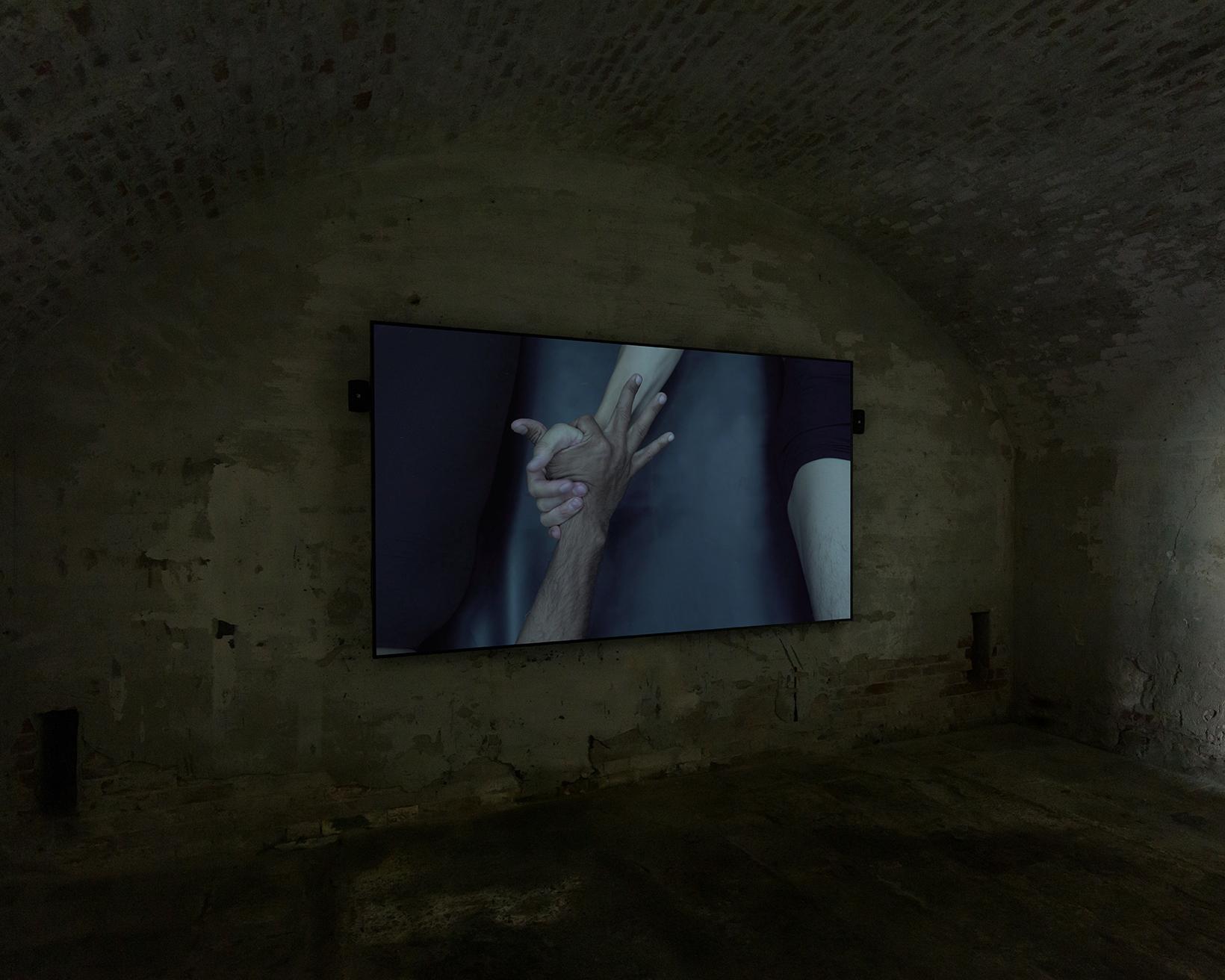

Haper's Bazaar: Lazarus, on view at the Arsenale, is a video installation dedicated to the late Singapore-born ballet choreographer Goh Choo San, who lost his life to AIDS a generation ago and Brazilian conceptual artist Jose Leonilson. It was already well received by both critics and audiences last year when you were selected as a finalist for the Korean Artist Prize by the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art.

Kang Seung Lee: While drawing is part of who I am, video requires collaboration and takes many aspects out of my control. Rather than judging my work as good or bad, I feel accomplished when I am just moving forward. I wanted to create a video that became meaningful only when experienced in an art museum, not anywhere else. Why does it have to be a video in an art gallery, not one we watch alone at home or one we share together at the theater? Why do I make artwork that some people constantly pass by and others generally do not appreciate as a whole? Lazarus was created with the belief that there are certain senses that can only be experienced when the viewer encounters a video in an art museum–from the sense of hearing, touch, and spatial perception, as well as the sense of sight. I wanted to present a work that conveyed an indescribable feeling to the audience, if they did not watch the whole video. For this reason a body appears on the screen, similar to the human scale, but at times becoming much larger and at other times becoming much smaller. I want to continue the talk about dancers that had a queer body at their core. On that note, I am currently preparing to work on the aging body of an elderly queer dancer.

Haper's Bazaar: The theme of this Biennale is Foreigners Everywhere. Having been born in Korea and currently based in L.A. after spending time in the Middle East and Latin America, do you define yourself as a foreigner?

Kang Seung Lee: Photographer Tseng Kwong Chi used to say “I am a permanent visitor,” wearing a ‘visitor’ badge on his chest wherever he went. This is true not only for the queer population, but also for everyone who deviates from mainstream history or social concepts like women or indigenous people. Now settled in Los Angeles, I identify as a gay, Asian immigrant. I often find that my myriad personal identities carry more weight in the US. However, having multiple identities allows me to better understand others, or at least try to. Who can fit perfectly into the framework of one country, one city, or one story? We are all foreigners.

Haper's Bazaar: I know that you have been in close communication with the artistic director, Adriano Pedrosa. What is the artistic vision you both share?

Kang Seung Lee: While my work is an attempt to discover excluded minorities and bring them back into the mainstream, Pedrosa approaches the concept quite differently. We all grew up with a mainstream education, and a colonialized version of knowledge. Therefore, he feels we need to overthrow this way of thinking altogether. Why was the Native American’s tapestry once considered unfavorable in the art world? I believe this Biennale is significant because it attempts to break away from this mainstream perspective.

Haper's Bazaar: I agree that colonialized knowledge is sometimes disguised in the word ‘taste.’

Kang Seung Lee: Of course, I have my own taste. Apart from the concept itself, there must be something aesthetically pleasing or displeasing. But I often ask myself, “Why do I like or dislike this?” People believe that taste is a unique area that others cannot invade, but that is not the reality. For example, if I saw some art and felt it was aesthetically pleasing, it would be the result of what I have learned since birth, not my individual originality. In that sense, ‘taste’ is a cruel word. The criterion of beauty has changed over time. I think recognizing that individual tastes are created within that criterion makes all the difference.

Haper's Bazaar: You once mentioned philosopher Emanuele Coccia’s theory that there seems to be a point where the approach of “‘the self’ we recognize is a ‘recycled version’ of a different existence,” which is closely linked to your work.

Kang Seung Lee: I was particularly impressed by Emanuele Coccia’s theory of the atmosphere. According to the theory, almost all matter does not escape into outer space but remains in the atmosphere. When a person dies and is buried or cremated, they become part of the land, air, and water. It means that everything once lived on Earth is still by our side, and these lost people are there as well, along with their forgotten stories. I have settled on the possibility that nothing completely disappears from Earth, and that a new story can be born at any time by being cultivated again.

Haper's Bazaar: From an ecological viewpoint, the human species is too insignificant and weak. Have you ever felt your labor-intensive work to be useless from this point of view?

Kang Seung Lee: From a macroscopic point of view, my life and work don’t mean much, but at the same time I believe they have significant meaning. Eventually, while we live within time, we can recognize and pursue what we are meant to do. We wonder how we can contribute in order to help our community and future generations. Realizing that everything I enjoy now was made possible by past generations puts me in that position. Additionally, I believe art can accomplish much in this finite life.

Haper's Bazaar: As a tribute to the forgotten, you have been applying labor-intensive media such as graphite, colored pencil, gold thread embroidery, and tapestries that require the use of your body to be completed. Apart from your general thoughts on your work, is there a fundamental reason for your attraction to media based on pain and suffering?

Kang Seung Lee: There probably is because pain and pleasure are connected. Why have people been sewing so much for such a long time? People feel moved when they see work completed through labor or someone’s pain and effort. Pain and pleasure are definitely connected.

Haper's Bazaar: Please describe a moment when pain and hard work are converted into pleasure in your art.

Kang Seung Lee: It gives me pleasure when I see something indescribable beyond my original intentions, as a result of gathering several works together. That is one possible perk of visual art. Do we need art to exist if we can explain everything logically? Art shines the most when it can’t explain itself or be explained. We wouldn’t need art if everything could be explained logically. Art shines where we cannot explain. Of course, art won’t bring a sudden change to the world. It’s a rather arrogant illusion to believe that art holds that power. I think the potential of art lies in making gradual, deeper changes, even if they happen very slowly. I, myself, have experienced that potential in my life. Because I still believe in that power, I can continue this demanding, lengthy, tedious work. I still believe in the power of art.

...