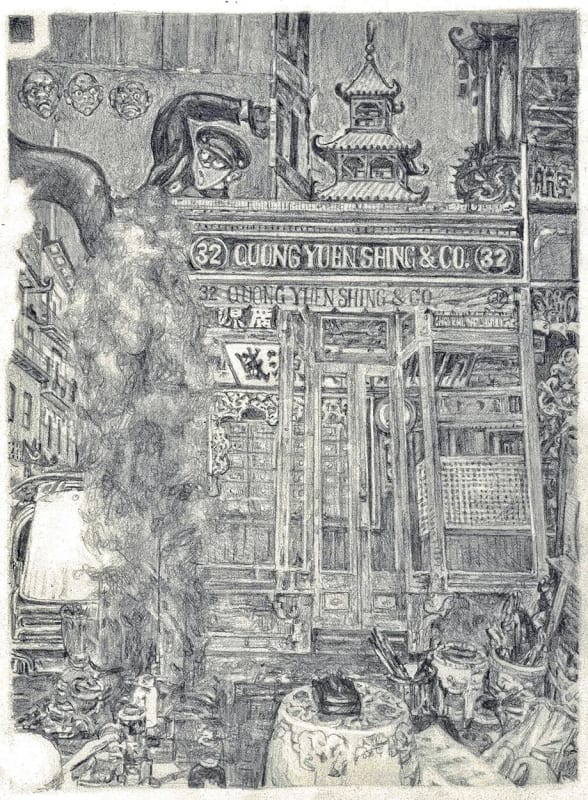

The works of Kang Seung Lee evoke the intergenerational care required to preserve queer legacies. Using fragile materials—plants that can wilt and die, loose threads that can snag, dried flowers that can disintegrate—the South Korea–born, Los Angeles–based artist captures the precariousness of life and the fleeting nature of memory. In his graphite drawings, Lee laboriously re-creates photographs of queer artists who died from AIDS-related complications, among them Martin Wong and David Wojnarowicz. Their surroundings are rendered in painstaking detail: painted Chinatown pagodas from Wong’s canvases are depicted tile by tile, and the fluffy blanket that envelops Wojnarowicz is rendered with scrawled shading. But only a hazy silhouette of each artist remains.

Lee’s work, with its focus on time and dissolution, is a natural fit for “Soft Water Hard Stone,” this year’s triennial at the New Museum in New York. The exhibition’s title alludes to the proverbial idea that, with persistence, small actions will eventually erode seemingly permanent structures. In Lee’s work, “hard stone” can be understood as the obstacles to queer liberation, and “soft water” as sustained collective effort.

When the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (MMCA), commissioned Lee to create a new work for “2020 Asia Project—Looking for Another Family,” he dedicated half his budget to purchasing publications on queer theory and queer artists from across the globe. The subsequent installation, Untitled (Library), 2020, took the form of a reading area featuring bookshelves lined with queer texts—a powerful statement in a country that has not yet recognized same-sex marriage. Developed in collaboration with Seoul-based literary critic Hyejin Oh—who purchased approximately 200 books about the history of queer culture in Korea—Untitled (Library) served as a corrective to a glaring absence in MMCA’s holdings. Lee’s intervention introduced queer history into the library of a national South Korean institution where, following the exhibition’s conclusion, the publications are now freely available to the public.

Lee knows that history is also found, recorded, and dispersed beyond books. Whether in collaboration with his peers or in visual conversation with his late predecessors, a sense of community is always present in his work. In his solo exhibition “Permanent Visitor” at Commonwealth and Council in Los Angeles this past summer, Lee opted to include a work by artist Julie Tolentino: Archive in Dirt (2019), a live cactus propagated from one that originally belonged to Harvey Milk (1930–1978), California’s first openly gay elected official. Like traditional collections, Archive in Dirt requires care and maintenance in order to grow and be available for others in the future.

Lee molded a pot and saucer for the plant using California clay mixed with soil from the garden of late queer filmmaker Derek Jarman, as representation wove an additional layer of queer history and presence into the archive Tolentino helped cultivate. Lee highlights the pebbles, plants, and other nonhuman organisms and objects that bore witness to the lives of Milk, Jarman, and anonymous queer Koreans. In so doing, he shows that the archive is not static but fertile, that its branches might continue to reach and grow.

This article appears under the title “First Look: Kang Seung Lee” in the November/December 2021 issue, p. 14.

...