In her article “Witnessing the In-visibility of Inca Architecture in Colonial Peru” (2007), Stella Nair describes how 16th-century Spanish colonists razed Incan art and architecture, replacing Indigenous culture with their own. Across the Americas and the Caribbean, the pattern persisted: Europeans destroyed artifacts of native creativity as they asserted their dominance over the people themselves. Nair writes about how contemporary Latinx artists are reclaiming their aesthetic past by embracing fragmentation and the partial histories they’ve received. The open-ended nature of abstraction appeals to many of them.

These painters, sculptors, photographers, and weavers are slowly reviving Indigenous forms of knowledge as they connect to their roots. Last year, Elizabeth Ferrer curated the revelatory exhibition “Latinx Abstract” at BRIC with the contemporary Latinx artists Candida Alvarez, Karlos Cárcamo, Maria Chávez, Alejandro Guzmán, Glendalys Medina, Freddy Rodríguez, Fanny Sanín, Mary Valverde, Vargas-Suarez Universal, and Sarah Zapata. The show featured paintings and sculptures that were outstanding in their own right—and reinvigorated the American canon of abstraction that has, for too long, been dominated by white Euro-American male artists.

In 2018, Marcela Guerrero curated “Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay: Indigenous Space, Modern Architecture, New Art” at the Whitney Museum of American Art. The exhibition suggested that European colonial culture did not destroy Indigenous culture at all—that precolonial forms live on as vibrantly as ever, through the work of contemporary Latinx artists such as William Cordova, Livia Corona Benjamin, Jorge González, Guadalupe Maravilla, Claudia Peña Salinas, Clarissa Tossin, and Ronny Quevedo. A special interest in precolonial architecture pervaded the show, and the focus on “Latinx” artists (a descriptor that eliminates markers of gender) also embraced the complex nature of identity for those who feel fragmented by a colonial past.

Contemporary Latinx abstraction doesn’t just look towards repairing the past, though: It also helps envision Indigenous futures. Using oral histories and research as starting points, artists use shards of the past to reconfigure their cultures for future generations.

Artsy spoke with five contemporary Latinx artists working in abstraction—Sarah Zapata, Ronny Quevedo, Lisa Alvarado, Tanya Aguiñiga, and Blanka Amezkua—to understand how they use abstraction to keep precolonial indigeneity across the Americas and Caribbean alive.

Ronny Quevedo

B. 1981, Guayaquil, Ecuador. Lives and works in New York.

Ronny Quevedo transforms personal memory and celestial imagery into abstract, geometric sculptures. Through his practice, he aims to repair the harms of historical forced migration of Latinx cultures across the Americas and Caribbean—his own family was forced to move from Ecuador to New York. His palette of gold, deep blues, and blacks creates an ethereal sensibility that suggests ideas of universal, personal, and cultural belonging.

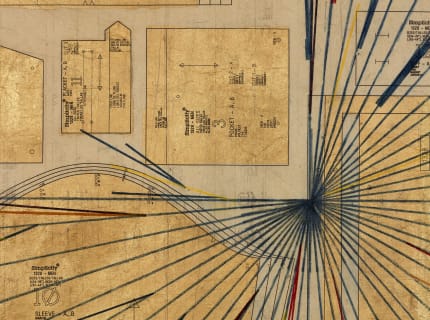

Inspired by his mother’s practice as a seamstress, Quevedo integrates sewing-related materials such as muslin and patterns into his work. “I also include linoleum tiles, copper, gold, and milk crates to represent a specific environment or an upbringing, as a type of imagined viewer or community that I have in mind,” the artist said. “So my process is often directed and influenced by those materials and the audience I want to engage with.”

The muslin scraps serve as a metaphor for an Andean culture that’s been shredded and discarded. One sculpture, el guarda meta de los cosmos (from the abyss) (2022), from his latest solo exhibition “entre aquí y allá” at Alexander Gray Associates in New York, on view through October 15th, is emblematic of his practice. The sparse sculpture resembles a minimal soccer field with two opposing sides. The piece uses copper tubing to evoke both exploitative labor mining in South America and the goal posts of soccer games his father played when he was young.

Quevedo first interacted with abstraction via precolonial South American culture. The Wari Feathered Panel (600–900) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art enchanted him as a teenager. He recalled its simple design with yellow and blue tapestries made of bird feathers. “That, for me, was always really striking because it was my first encounter of representing geography and place through an abstract form,” he said.

The Cubist paintings and sculptures of Uraguyan modern artist Joaquín Torres-García also left a mark on Quevedo’s practice. “There is a tussle between the two—between defined imagery and undefined imagery. He is also someone looking at mapping as a site of play and challenge,” Quevedo said. Torres-García’s practice has helped the artist think through his personal history and the larger colonial past, fusing personal iconography with that of precolonial indigenous cultures.

Abstraction allows Quevedo to explore Andean culture without trying to resolve its fragments. The artist honors his personal experiences along the way. He believes that abstraction offers a forum “for discussing liminal spaces, temporality, and opacity. This multiplicity posits a redefinition of abstract work and what geographies and histories get included in that reimagining.”

...

Read full article at artsy.net.