“Ronny Quevedo: offside,” one of the latest exhibits to open at the University Art Museum, is deceptively sparse on first blush.

The gallery walls aren’t densely packed with works; yet, every inch of the space is thoughtfully used and considered through site-specific installations and works on paper.

In the largest installation, titled “fuera de lugar,” vinyl red and blue lines form a diagram from floor to ceiling on two of the gallery’s arched walls. The title translates to “out of place” and is a reference to a rule in soccer that restricts a player’s movement. The stark lines are reminiscent of a gymnasium, though certain breaks in the lines reference a sewing pattern.

Quevedo weaves those two pieces of his family’s identity together, especially in works like “Ode to Liga Deportiva Guayaquil de Indoor Futbol (Working Class Epistemology).” Thin wooden planks are lined up on a large panel and topped with flecks of red, white, orange and yellow, creating a frantic pattern. Dress patterns peek out from gaps between the planks.

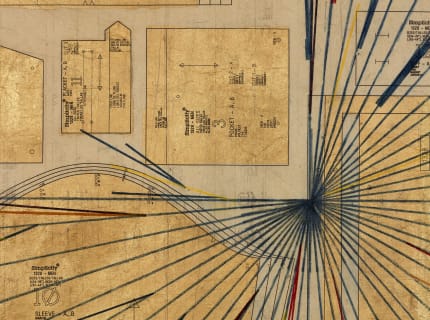

In another piece, “el back-centro,” the references are layered together more ambiguously. Dress patterns mounted on muslin are depicted in gold leaf and placed so that their lines create a shape reminiscent of a field. Black thread sewn on top is a possible reference to certain field lines.

Elsewhere in the exhibit, Quevedo considers cultural structures and traditions in ‘a mother’s hand,” an installation that features a pyramid shape made of stacked plywood boxes. The shape references platform architecture and agricultural terracing of the Andes, as well as stadium bleachers. It also pays homage to pre-Columbian textile work.

The piece is on the first floor of the gallery and helps to ground the entire exhibit within the gallery space. Quevedo also placed works on carbon paper on each of the gallery’s four walls, denoting the four cardinal directions. These help to orient the viewer, even as installations like “fuera de lugar” disorient and raise questions about belonging and finding one’s place in the world.

Quevedo’s work pulls together the personal and the political and pairs well with video installations by Rodrigo Valenzuela, also on view at the museum.