The show currently on view in the Central and South El Pomar Galleries at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center is Ronny Quevedo’s solo exhibition at the line. It includes works on paper and muslin, as well as a site-specific installation. As the Curator of Contemporary Art Katja Rivera explains in an accompanying pamphlet, the exhibition is a celebration of Quevedo’s recent artistic practice. His works weave together layered histories from across the Americas, speak to the formation of diasporic identities, and use materials and processes connected with immigration both past and present. [1] As a result, Quevedo blurs geographic, historical, and temporal boundaries to highlight the complex narratives of the movement(s) associated with historically marginalized peoples. Before the exhibition opened, I had the pleasure of meeting Quevedo and Rivera and viewing the galleries during installation.

Quevedo (b. 1981 in Guayaquil, Ecuador) is a contemporary Latinx artist living and working in the Bronx, New York. He holds an MFA from the Yale School of Art (2013) and a BFA from The Cooper Union (2003). He has exhibited across the U.S. and has had numerous solo exhibitions. According to art historian Ananda Cohen-Aponte, his works reference Andean and Mesoamerican cultures, soccer fields, gymnasium floors, the Mesoamerican ballgame, and the artist’s personal migration story from Ecuador to the Bronx. [2] Within his body of work, it is the concept of movement that ties sports and play to migration and survival.

Consistent with previous exhibitions of Quevedo’s works, at the line presents art that abstracts movement through time and space in its materials, processes, and compositions. To highlight the effects of colonialism and community displacement on the immigrant working-class in the Americas, the artist uses unconventional materials such as dressmaker’s pattern paper, shoelaces, milk crates, wax, enamel, contact paper, gold and silver leaf, drywall, vinyl, and gesso. Through a subversion of this mix of “high” and “working-class” materials, the artist elevates common household items to monumentalize them. [3] As such, most of the artist’s works in the exhibition extend beyond the realm of traditional painting and drawing.

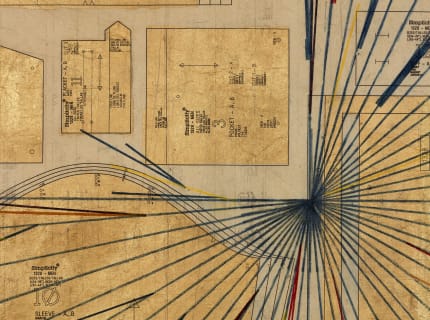

Quevedo depicts a blurring of time and space via dismembered bodies—as is the case with Zoot Suit Riot at Qoricancha (2017)—and fractured geographical spaces—such as revolutions abound (Estadio Olímpico Atahualpa) (2019)—to suggest notions of displacement and the fusion of past and present histories. For Zoot Suit Riot at Qoricancha, in particular, the artist collages and abstracts a zoot suit—a 1940’s symbol for men of color in the U.S. claiming public and political space—using a jacket’s pattern paper parts, and the title also makes reference to the Incan temple Qoricancha (c.1200) in Cusco, Peru. [4] When looking closely at this work, we notice a sleeve here and a breast panel there by following the numbers, directions, and dotted lines of each panel to slowly rejoin each disassembled part back together. To elevate the paper’s material importance and to blur time and space further, Quevedo overlays gold and silver leaf on chosen areas to simulate the pattern’s reflections. As a combined whole, the artwork and its title imply a complicated history of broken spaces and lost time due to disjointed movement and immigration across borders. [5]