I AM IN ART SCHOOL, my first year in an MFA program. 1999. I am the only Black student in my painting-major studio class. Our professor is showing us slides (yes, actual slides) of paintings. It is a classic art-school moment. A group of young people, an older professor, flashes of light on a studio wall. Paintings, one after the other, that have something to do with the current lesson and have a particular interest for people in the class in terms of technique and subject.

An image of a Klansman appears on the wall. I gasp. The slide seems to be up for much longer than all the other slides.

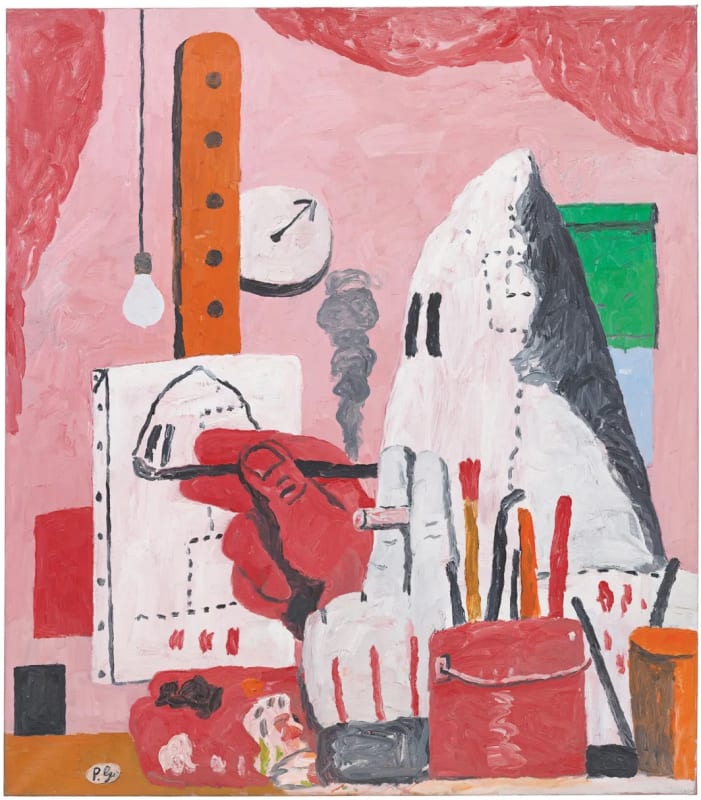

It is a painting of a classic theme: the artist in the studio. Here, the artist wears the white robe of a member of the Ku Klux Klan. It is painted in a cartoony, clumsy, almost goofy style, as if it were from the funny pages. Everything in the picture seems swollen. The figure holds a chubby cigar with gray smoke rising from it like a little tornado. He holds a brush in his bright-red hand, which is trained on a little canvas on an easel. He is occupied with the act of painting, and, from the rendering on the canvas, it is clear that he is painting a self-portrait. I cannot believe my eyes. I am appalled and stunned that we are looking at this image. I cannot fathom why someone would paint this subject in this manner. Why is he showing us this? I thought. Why do I have to sit here and look at this picture of a KKK member?

I hear my teacher say, “Philip Guston, 1969, The Studio, about six by six feet, oil on canvas.”

“Why are you showing us this?” I ask. Everyone looks at me.

“This painting is the beginning of Guston’s departure from abstraction and return to a new kind of figuration.”

“And was he in the Klan?” I ask.

“No,” my professor says. “Although he uses this figure as an alter ego.”

“He’s white?”

“Yes. And Jewish. There was a lot of controversy about Guston. You should examine it. Next slide.”

I scribble down the name. An alter ego? A Jewish artist painting himself as a Klansman? I am not able to pay attention to the other artists in the slide presentation. The Guston picture is all I can think about. I feel certain that my classmates can smell my anger.

I spend the rest of that day in the school library looking at everything I can dig up on Philip Guston. I look at all of the work I can find. I learn about his trajectory, his work as a muralist, his time in the WPA, his success as an abstract painter, his struggle, his loss of confidence, his return to figuration. I read the reviews of the 1970 Marlborough Gallery, New York, show that included The Studio. I read about his long teaching career.

I learn about his work Drawing for Conspirators, 1930, which shows a group of Klansmen lynching a Black man while a large hooded figure in the foreground slumps in what seems to be regret. Seeing that work from thirty-nine years before he painted The Studio signals to me that this imagery has been with him for a while. I learn that I am not seeing what I think I am seeing. Instead of evidence of an artist’s racism, I learn that, for the first time in my life, I am seeing a white artist—one of the giants of American art—grapple with his own complicity in white supremacy. I learn that I am seeing a great abstract painter turn his back on abstraction—and all that word contained in that moment—to engage with his whiteness and complicity in racism. Instead of putting the Klan hood on someone else, in 1969, he puts it on himself. He cloaks himself in the everyday violence and racism of the time in which he lives. (It’s no accident that the figure in The Studio is “red-handed.”) Unlike those in Conspirators, the hooded figures in the later Guston paintings (Edge of Town, 1969, and Dawn and Flatlands, both 1970) are not pictured engaged in mayhem. Rather they are driving, smoking, and hanging out together. They’re doing ordinary things.

I learn. And I learn not from a place of comfort or protection but from one of challenge and analysis. I learn that my feelings about art are a catalyst for engagement—not an end in themselves.

Right now, there is no shortage of outrage about art, paintings, and the question of who has the ability (or even the right) to portray particular subjects. Images can generate powerful responses. People claim that images do violence and that the public—especially the disenfranchised—should be protected from images that would harm them. I wonder how deeply people interrogate their own responses to what they see, if they go beyond what they feel to what they think. I wonder if anyone is willing to do the sometimes challenging work of learning from and engaging with artworks, particularly those we term “difficult.” I wonder if an artwork is an opportunity to reexamine one’s selfhood. I wonder if museums are willing to educate their publics—as well as their own staff—to help them understand the works they present. I wonder if people know that when they are talking about an artwork, they are actually talking about themselves.

I don’t really wonder about those things, to be honest. What I am doing is lamenting that they are gone.

The popular understanding is that art is a personal activity rooted in self-expression. This is why so many artists are dismissed as navel-gazing or self-obsessed. A better understanding is that the artist is a conduit through which the entire culture is filtered. Artists are not simply expressing themselves, they are expressing an embodied experience of our shared culture. Artists are responsible for what they make, of course. My point is that artworks give us a reason to reflect on the time of their making. What is happening at that moment, the original context of the work of art, is something that people who make exhibitions are trained to glean and represent for contemporary audiences, so that objects from the past are not viewed in a historical vacuum. To claim that one’s whiteness prevents one from presenting works of art that are about whiteness troubles me as much as the need to present Black voices as interlocutors for a discussion about race.

Because it must be said that there is a specious notion that race is solely about Black people. White people have been allowed to claim that because they are white, they do not understand race, cannot understand race, and should not ever discuss race. If race ever comes to the fore, then, white people insist, Black people need to be brought in as the authority and must educate white people about race. To my mind, this absolves white people of any responsibility to examine their own racial identity and allows for the persistence of the myth of white racial innocence. White people know what racism is, and they know what white supremacy is. They are the organizing principles of American life. Black people don’t need to explain to white people the system of oppression white people created to ensure their dominance. But white people often outsource their emotional labor and guilt about white supremacy to Black people so they can claim, “I could never understand what it is to be Black.” The myth of white racial innocence is married to the lie of inscrutable Blackness.

White people have a race. Guston is the first artist I ever saw make paintings about white complicity and silence in the face of white supremacy, putting on a Klan hood to examine his white selfhood. As Toni Morrison said to Charlie Rose back in 1993, “If you can only be tall because somebody’s on their knees, then you have a serious problem. And my feeling is white people have a very, very serious problem, and they should start thinking about what they can do about it.” Guston’s paintings are an opening into Morrison’s call for white thinking about what whiteness is and does.

It is telling that, at a moment when so many have been demanding that white people and institutions address their complicity in white supremacy, the work of an artist who did exactly that, in 1969, is up for consideration in a retrospective. Also telling is the fear that white people have of said work being “misunderstood” as racist or evil because of the current challenges to Confederate statues and the plethora of images of state violence against Black people. That fear should not prevent them from doing their work, which is to present objects in context in a way that speaks to all of their constituencies, internal and external, without condescension or contempt.

Guston made a choice to reengage in the world and to image its circumstances. He took on his own whiteness and complicity and silence and showed them to the public. He could have kept making the luminous abstract paintings for which he was known, but he had the unfinished business of the vile world to address. He implicated himself—red-handed, stumbling and swollen with potential violence—at a time when he did not have to do anything. He pointed the finger at himself and made it clear that whiteness carries a legacy of violence of which he was a beneficiary.

That is what accountability looks like.

...

Read article at artforum.com.