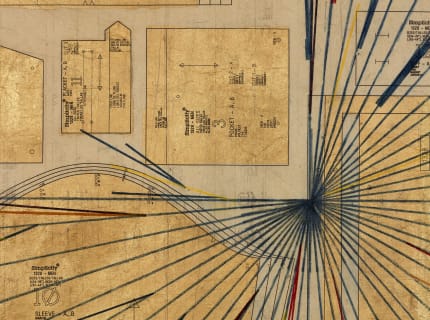

Ronny Quevedo’s work uses abstraction to address personal and political themes with suggestive intricacy. His drawings, prints, and installations scramble the visual architecture of diagrams and maps into zigzagging networks of line and color. In ULAMA-ULE-ALLEY OOP (2017), for example, an enamel basketball court diagram has been chopped up and overlaid upon the faint graphite blueprint of a Mesoamerican ball field. In every measure of zero (tropic of cancer) (2018) an atlas’s spherical longitude lines and thin streaks of white rectangle are embedded in moody-blue washes of dressmaker wax paper. Palimpsests of demarcation, the works read as pleasing abstract compositions while also containing poetic hints and traces of the objects—athletic fields, geographical maps, Incan quipus, dressmakers’ pattern sheets, milk crates—that cultures use to organize and measure themselves. Quevedo’s ingenious blend of figuration and abstraction belongs to a vital, if undercredited, tradition of abstraction by nonwhite artists that includes figures such as Jack Whitten, Alma Thomas, Carmen Herrera, Byron Kim, and Cecilia Vicuña. In a genre often thought to be transcendentally universal, Quevedo’s abstractions express in acute and evocative ways the particulars of his experiences as an Ecuadorian immigrant to the United States.

—Louis Bury

Louis Bury: Your father, Carlos Quevedo, was a professional soccer player, and you’re perhaps best known for work that depicts altered and abstracted athletic-field diagrams. What’s the personal, political, and aesthetic import of sport for you?

Ronny Quevedo: My dad played professional soccer in Ecuador from the late 1950s to late 1960s for division one teams such as Macara and Independiente. After we moved to New York City in the early 1980s, he served for over twenty years as a referee for various organized leagues, especially ones that played in Queens’s Flushing Meadows Corona Park. Refereeing was not his full-time job, but he did it every weekend, year-round, and was renowned within these circles. My brother and I would accompany him most weekends, playing with other kids on the sidelines and running the halls of an empty school building.

LB: What impression did those experiences make on you?

RQ: The games were part of a well-organized enclave of South American and Central American amateur soccer leagues. The leagues had rules about uniforms and playoff systems; spectators paid entry fees to watch the games and could buy Ecuadorian dishes like muchines, empanadas, and fritada. Noticias del Mundo, a local newspaper, reported on the games. The entire enterprise existed on the margins of mainstream culture. Soccer, in particular, was nowhere to be seen in US pop culture at that time. This environment provided my initial perspective on sport and play as forms of cultural expression. From it, I came to understand the political implications of making space for oneself and that economics was a matter of resourcefulness. It also drove home the elasticity under which people of color operate, particularly in the way we move between multiple languages and code-switch within the dominant language.

...

Read full interview at bombmagazine.org.