It was a short walk from Samson Gallery, where I attended Steve Locke’s opening reception for his solo show “School of Love,” to the Gallery Kayafas, some two doors down, where I viewed “Family Pictures,” his second and concurrent solo show. “Family Pictures” is a compelling show, not because Locke deviates from his usual painting and sculptural practice, which is on full display in “School of Love,” but because he enters new territory, utilizing the medium of photography in conjunction with appropriation and installation strategies, fusing this show into a scathing critique of our alleged post-racial society.

Locke was on sabbatical when he decided he had to make work in response to the increasing number of televised killings of black individuals at the hands of U.S. law enforcement. Utilizing photography to create a series of images as part of a very methodical and purposeful installation, Locke lays bare the core issues that underlie the inability to move forward on race in this country, connecting the events of the past with the detached spectacle we are witnessing today.

Locke lulls us in, setting up the show so that the uninitiated viewer comes to the work unaware, and even after reading the information on the wall at the first switchback on the ramp leading up to the exhibition, one is certainly not prepared for what is to come. The gallery has several rows of vitrines that remind one of a triage room, or tables where evidence from an investigation is laid out for examination after a traumatic event. Locke arranges his series of images so the viewer will be fully focused on what is being presented as they move along the tables. The images on the wall repeat in larger format the images that are presented in the vitrines.

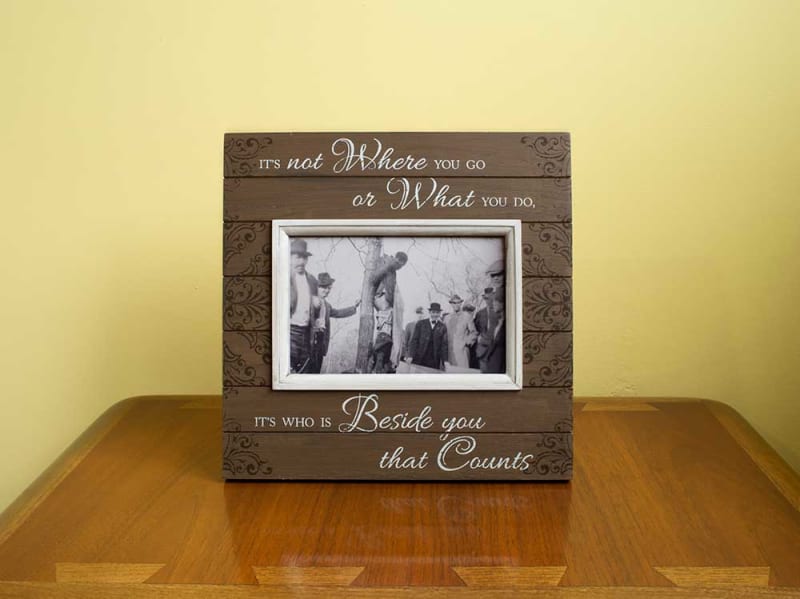

Starting with the first vitrine, an image of a diagram of a slave ship presented in a store-bought, ceramic table-top frame with the phrase “Our Honeymoon” inscribed on it and a relief of two flip flops photographed on a 1960s-style end table in front of a red wall, one is provided with the historical orientation and aesthetic platform in which the images will be presented. This will be a history lesson. In the next image, and the ones that immediately follow, the work evolves from that initial distant reminder to the 20th century, presenting a series of images within these sentimental frames that reveal the full horror of the show. Images culled from souvenir postcards celebrating lynchings, with insipid phrases substituting for the captions that were often included on the original postcards that freely passed through the mail until that practice was banned in the early 20th century, jar the spectator and question their complicity in the event: a charred corpse in a frame that reads “Always & Forever”; two hanging bodies flanked by smiling white males with the phrase “Who wouldn’t want to be us”; and another with two bodies suspended over a crowd of men and women with the phrase “I can’t believe we did that.”

The color shifts represent different rooms in a house, placing them in a shifting domestic context. The 1960s-era end table is reminiscent of the monumental shifts that were occurring regarding civil rights at the time, but the contrast between this historic imagery from the past fused with the contemporary frames provided the reminder that there has essentially been no progress on this fundamental issue.

What Locke presents is evidence of complicity. As a white viewer, I am left with a simple fact: this existed and still exists. It also presents the very real fact that I can’t really know how it feels, but I can look at this work and clearly see the issue. I cannot explain it away, I cannot pretend it didn’t happen, I cannot pretend to understand. Most of all I cannot pretend that the problem has been solved and that I am somehow not part of the problem. In an interview with Manthia Diawara, the late writer and critic Édouard Glissant said, “A racist is someone who refuses what he doesn’t understand. I can accept what I don’t understand. Opacity is a right we must have.”

Ever the teacher, Locke provides a space at the rear of the gallery that includes a table with books on the racial history of the United States. The niche includes a blue neon piece titled “A Dream,” meant to mimic police lights (part of his piece for the MassArt biennale faculty show that listed the names of the 262 unarmed African Americans killed or who died while in police custody during Locke’s sabbatical from 2014-2015). Locke’s table of books is a space of contemplation and, if one wishes, investigation. It is here that Locke generously offers viewers the resources and opportunity to understand their history and their role in that history. It’s a painful and necessary show and as an artistic gesture provides the privileged viewer a way to access information that few media outlets provide. It rises above the chatter and whitesplaining and offers a sobering critique, placing the responsibility on the viewer as to how they plan to proceed.

...

Read review at artpulsemagazine.com.