In 1962, multimedia artist Regina Silveira was studying under Iberê Camargo (1914-1994), in his native city of Porto Alegre. Iberê controlled each student in the room with eagle eyes. A classmate standing next to Regina was delicately painting something with a very expensive sable paintbrush. This annoyed Iberê so much that at one point he could no longer control himself, so he yanked the paintbrush from Maria’s hand, told her that this was not what painting was about and threw the paintbrush out the window. “We froze, watching the paintbrush fall on the top of a moving streetcar,” Regina recalls. “Then he asked for a wide paintbrush with hard bristles and squeezed all of Maria’s paints on her palette. He remained on his feet and started painting over what she had done, using thick brush strokes.” Regina says that in a few minutes, the original painting had been totally transformed and the result was marvelous. “I’ll never forget that expensive sable paintbrush flying out the window,” says the artist.

This was the start of the professional life of this lively, curious creator. She has always been guided by poetic investigation and freedom, with an attitude that constantly questions everything that is traditional or consolidated in art. “The artist does not come up with solutions; the artist asks questions and can also provoke tension,” she explains. This is why she is involved in so many types of artistic expression, ranging from photography to painting, from posters to involvement in city architecture. Regina is as interested in subverting the systems of artistic perspective as she is in representing the shadows that are created without revealing the element that causes them. She has been engaging in urban landscape since the 1990’s. Her most recent work, Tramazul, can be seen on Paulista Avenue [in the city of São Paulo] until January 2011. Regina transformed the ‘box’ that houses Masp, the São Paulo Art Museum, into a huge embroidered diagram of blue sky. “I feel very gratified when I see that art spaces held sacred are giving way to street manifestations, in a closer relationship with the public.” Painter, illustrator, engraver, and graphic artist, Regina is also a retired teacher of the Fine Arts Department of ECA-USP. As such, she gives credit to academic experience. “I managed to produce experimental works of art and objects thanks to research grants from such agencies as FAPESP.” Next year, the Edusp publishing house will launch the book O Outro lado da imagem: a poética de Regina Silveira [The other side of the image: the poetics of Regina Silveira], by Spanish art critic Adolfo Montejo Navas. Below are excerpts of Pesquisa FAPESP’s interview with Regina Silveira.

Classic author Pliny the Elder (23 to 79 A.D.) defined the language of images as a shadow, “the sign left on the wall by a lover who has left.” This has a lot to do with your art, doesn’t it?

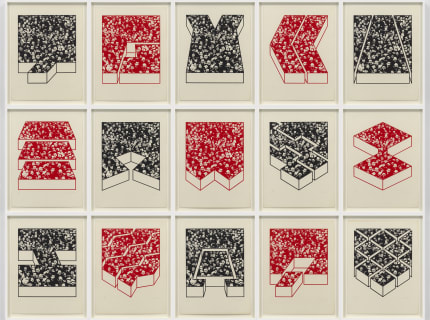

The interpretation of this metaphor on the origin of painting, which is almost a poem, is not that simple. The first image or original pictorial representation is not exactly a copy, a direct registration of something real; this is a more complex issue. That loving – and disciplined – gesture of fixing a shadow of something real, which is not an image in itself, but a vestige and a sign of absence, by means of an abstract contour (Leonardo warned that contours did not exist in reality) makes Pliny the Elder’s metaphor something much more intricate. This has nothing to do with the images that appear in various cultures; it is related to the enormous power of provoking the imagination to other considerations on the relationship between what is real and images – and, inversely, at least in my opinion, on the function of images within what is real. Anyway, silhouettes are representations in their most basic and rudimentary state. Why did I get interested in silhouettes? The why is linked to the ambiguity and the mystery that I have found in these images for a long time. Silhouettes seem simple, when we think of them as dark, filled-in contours – but they are actually very ambiguous and appropriate for several phantasmagorias. The shadowy silhouettes have always led to extraordinary games of imagination, in a secular manner, in different art forms. Silhouettes that represent shadows conserve absence-related data that real shadows have, where they are not images but rather signs linked to a source; they are vestiges and signs with time and memory implications. I have always been interested in the mental and temporal relationship that shadows stain with their present or absent references. In short, this is a vast field for poetic operations, which I have always thought of in terms of substitutions and distortions. When does this begin? After working for some time on distortions of the artistic perspective, on photographic images that I solved mostly with contours, as exemplified by Anamorfas (1980); I made a set of four photograms (Enigmas, 1981) in which I covered objects photographed with the silhouettes (shadows) of other absent objects – to assemble series of visual ideograms, with combined and enigmatic meanings. My early art also includes the series of prints called Dilatáveis (1981), where the silhouetted shadows were proportionally much more extensive in relation to the small photographs of politicians, soldiers, and executives, which I had cut out from newspapers and magazines published back then. In the following years, the shadows and the silhouettes grew to environmental proportions, as exemplified by the installation In absentia MD shown at the 1983 São Paulo.

...

Read full interview at revistapesquisa.fapesp.br.