Ricardo Brey’s recent exhibition, “All that is could be otherwise,” comprised mainly recent collages on drawings and photographs, but its physical and conceptual centerpiece was a sculptural work that dates to the dawn of the millennium. For those unfamiliar with the Cuban-born artist who rose to prominence in the 1980s as a founding member of the avant-garde Volumen I collective, Birdland, 2001—a large nest made of old coats cradling several ostrich eggs and a swanlike saxophone—introduced two of Brey’s hallmarks: a strong association between nature and music (specifically Afro-Cuban and American jazz: in this case, Charlie “Bird” Parker) and his penchant for salvaged materials.

Made shortly after the birth of his daughter, Birdland also provided useful autobiographical context. Describing the nest’s saxophone occupant, Brey has pointed out that the instrument—surprisingly—was invented by a native of Belgium, where Brey himself has lived since 1992. Other materials like scattered buttons, broken dishes, and rusty South Dakota license plates (these last items collected on a Lakota reservation where Brey spent time in 1985), reference the importance of recycling in the artist’s native Cuba, where repurposing refuse is less an ecological concern than a survival skill. Brey’s well-worn or distressed found objects give this assemblage, and his work in general, a sense of authenticity and soulfulness that is present neither in Duchamp’s pristine appropriations nor in Arte Povera’s metaphysical interpretations of poverty.

Appreciated in this context, Brey’s most recent collage-based pieces, all dated 2016, profess a profound connection to his homeland. Photographed in Cuba and printed on canvas, board, or paper, large sepia-toned images of tree roots and stumps allude to deforestation, an environmental problem that dates back to colonial-era sugar plantations and that remains a major issue for Cuba today. By decorating photographs with small found objects, Brey honors ancient trees in shrine-like assemblages. The massive root system depicted in Mono-no-aware is garlanded with sparkling mirrored stars. In Portrait two small cowrie shells and a leather strap glued onto an image of a hollow tree suggest a reproachful, anteater-like totem. And in Voyage, Brey underscores the importance of networks and connections by collaging toy train tracks and spools of string onto a photograph of the base of a tree.

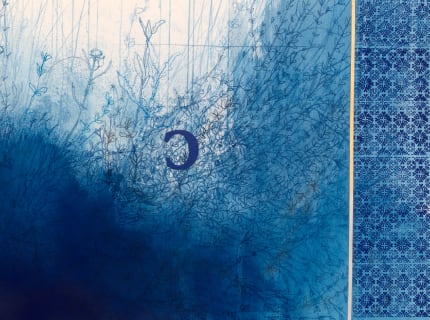

Bringing language into the mix, Brey features texts such as excerpts from a Spanish translation of Galileo’s sixteenth-century lectures on Dante’s Inferno in four large drawings in pencil, ink, or graphite, also from 2016. Here, collaged elements like small metal stars and watch wheels lend a navigational aspect to compositions made largely of concentric and overlapping circles. However, allusions to logic and science are confounded by fragmented, backward, and upside-down text (handwritten and collaged), which is often obscured by cloudy smudges of ink, graphite, or pigment. In Inferno, the most commanding of the drawings on view, mirrored letters affixed across an ominous gray-black haze spell out the title of the work as two separate words: INFER and NO. Inserting the viewer’s reflection into a murky confusion, Brey implores us not to make any too-rational deductions. If these drawings are indeed maps or diagrams, they do not chart an easy linear path. On the contrary, his swirling, celestial-inspired compositions suggest emotional and mystical journeys.

—Mara Hoberman