Melvin Edwards has been welding sculpture for more than five decades and bearing witness to the continuing history of race relations in the United States. His recent works include incisive new examples of his iconic “Lynch Fragments” series and monumental public projects installed in various locations, including Japan, Senegal, Cuba, and the U.S. Edwards’s interest in architecture and his commitment to abstraction as a meaningful form of expression are manifest in his metal sculptures, large and small alike. A major retrospective, organized by the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas and recently on view at the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University, afforded an opportunity to consider how the later works evince the culmination of a creative life that has produced a powerful body of work and taken Edwards to far-flung locations. These more recent works have links to major themes in Edwards’s career. Many are dedicated to artists known to him, such as Justice for Tropic-Ana (1986)—dedicated to Cuban artist Ana Mendieta—while others celebrate the lives of renowned African Americans, and a few examples are devoted to civil rights events. The “Lynch Fragments” are the predecessors of a remarkable group of large-scale works on public sites. Edwards has returned repeatedly to the “Lynch Frag - ments” throughout his career. The latest examples are larger, more varied in their elements, and more confrontational.

Born and raised in Houston, Texas, in a segregated community—interwoven with a five-year residence in Dayton, Ohio, during his childhood—Edwards did not experience the full impact of segregation in his youth. In 1953, he was one of two students from his all-black high school to be selected to take art classes at the Houston Museum of Fine Arts. Moving to Los Angeles offered a major revelation about racial tensions. Edwards studied at the Los Angeles County Art Institute (currently Otis Art Institute of the Parsons School of Design) and graduated from the University of Southern California in 1965. For the next two years, he taught at Chouinard Art Institute (now California Institute of the Arts). From his childhood fashioning of tomahawks to his discovery that his ancestry included an African blacksmith working as a slave in colonial America, Edwards has always sought to “understand forms.” He considers himself “largely self-taught as a person.”1 African American sculptor David Hammons told an interviewer: “I was influenced in a way by Mel Edwards’s work. He had a show at the Whitney in 1970 where he used a lot of chains and wires. That was the first abstract piece of art that I saw that had cultural value in it for black people. I couldn’t believe that piece when I saw it because I didn’t think you could make abstract art with a message.”2

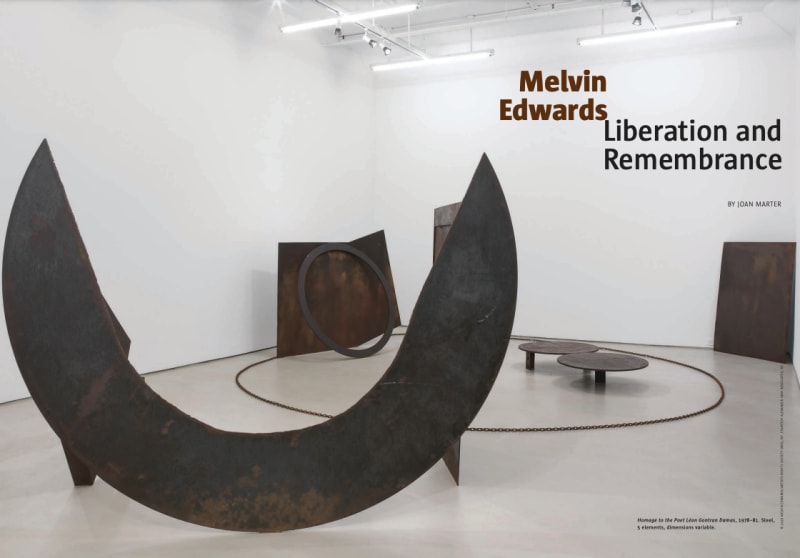

Edwards’s works have always been about conveying a message. From the 1960s on, he wished to counter the predominant formalism of art discourse. He notes, “I encountered the formalist rhetoric that was being taught about art. I later realized that the history of art was contrary to that rhetoric. All of the history of art showed that one could make art out of or about anything.”3 He considers geometric forms part of our visual experience and often incorporates actual objects, mostly in metal, within the fabric of his constructions. In large-scale pieces, he also joins recognizable chains with rectangular, columnar, and circular forms. As Edwards sees it, these works embody “the scope of human perception.” Having studied architecture, and worked with architectural tools, the concept of creating shelter and transforming space became an essential aspect of his worldview. While Edwards does not believe that art can change the world, he envisions that art, particularly public art, can be a positive force. After moving to New York City in 1967, Edwards exhibited at the Studio Museum in Harlem. Soon after, he joined with William T. Williams, Billy Rose, and Guy Ciarcia to make wall paintings in Harlem. The Smoke - house collective used brightly colored geometric forms to transform environments. In 1970, Edwards was the first African American sculptor to have a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Edwards devoted himself to the history of racial interactions and the visual culture of Third World countries, which resulted in travel to Brazil, Morocco, Nigeria, Ghana, Zimbabwe, Mexico, and Cuba. With a special devotion to Africa, which he first visited in 1970, he continues to spend months every year working in Senegal. Some of the largest “Lynch Fragments” were made in Africa. From the first examples to the current series of welded constructions that he began in 1978, the “Lynch Fragments” have been modest in size, featuring recognizable objects and instruments associated with sculpture production that could also serve as potential weapons—chains, knives, and railroad spikes. The first “Lynch Fragments” suggest oppression. Recent examples are more varied in theme. Some relate to historical conflicts, including Iraq (2003). These relief sculptures, measuring around 12 inches in length, are always hung on the wall one by one. Placed at eye level to the artist’s own height, the “Fragments” are both intimate and intimidating. Although Edwards had no direct exposure to lynching, he was certainly aware of its history and the struggle for civil rights. He created the “Lynch Fragments” in order “to discuss something violent—murder, general abuse, kidnapping, to the destruction of all human rights.”4 The imagery of chains combined with disks and other geometric forms continues in Edwards’s recent public sculpture. He has considered the role of his public work: “Art related to architecture and making life better for living. If we can give up war then it’s how to make life.” These public sculptures demonstrate Edwards’s versatility in creating outdoor projects for various sites. In 1993, he was invited to participate in the first Fujisankei Biennale Sculpture Competition in Japan. Asafo Kra No (1993), which was commissioned by the Utsukushiga-hara Open-Air Museum and won the biennial’s grand prize, includes a chain, a series of disks, and rockers. With this work, Edwards returned to painted steel, which he had not used for decades. Column of Memory (2005), a steel sculpture installed in a public park in Saint Louis, Senegal, was fabricated in Dakar. The work, which features a squared column flanked by upright chains, both memorializes the shackles of slavery and sug - gests that this past has been overcome. As Edwards sees it, his use of chains can refer to bondage or suggest a connection between disparate forces. This work anticipates the monumental Point of Memory (2010–13) in Santiago de Cuba, which is Edwards’s largest version to date of a composition joining chains in vertical formation with a column. Transcendence, dedicated in 2008, was commissioned to honor the first African American graduate of Lafayette College. David Kearney McDonogh, who was born into slavery, graduated in 1844 and became a physician, practicing in the New York area. McDonogh’s life transcended his early years, and the forms chosen by Edwards allude to this personal history by including chains joined with large geometric forms that glisten in stainless steel. Realizing that the dull surface of the steel needed to be worked, Edwards created “chiaroscuro” effects on the metal. Through grinding and polishing, he transformed the surface. The sculpture is 16 feet high, muscular, and imposing on a raised setting outside the library of Lafayette College. It seems that Edwards has determined to take the strength and message of his smaller “Lynch Fragments” and realize them in public settings. On a college campus, this monumental form dedicated to an African American student serves to remember a brave and determined young man. Though the piece includes chains, the dominant effect as conveyed by the stacked geometric forms is of stalwart resolve. The large arc of metal that dominates the work may allude to the trajectory of McDonogh’s career. Edwards points out that in this work his use of forms comes together, and he considers the piece one of his most satisfactory accomplishments. Point of Memory, dedicated 2013 and standing 18 feet tall, is installed in Parque de la Beneficiencia, Santiago de Cuba. This sculpture was fabricated in steel at a foundry at the Fundación Caguayo, directly from Edwards’s two-foot-high maquette, with the sculptor advising through telephone and e-mail. His involvement with Cuba was encouraged by his friendship with Ana Men - dieta, with whom he first visited Cuba in 1981. Edwards recalls, “I met Wifredo Lam. We traveled all over Cuba; we went to Santiago…On that trip I could see that Cuba was having a hard time. But it was much worse when we were there later.”5 Mindful of the African diaspora, Edwards notes, “You can see that the African influence in Cuba comes pretty specifically from two regions: the region of the Congo, and I say region, not country, because it’s that general Bantu-ish part of African culture; and then the Yoruba region. It’s the same in Brazil and in Haiti. This kind of specific cultural influence is something you can see in the United States as well.”6

Recently Edwards was awarded a commission for an as-yet unrealized memorial for Vinegar Hill in Charlottesville, Virginia. This historic African American neighborhood was demolished in 1964 as part of an urban renewal program, and Edwards proposed a stainless steel sculpture that is expected to be 12 feet high. Having met with community members of Vinegar Hill, Edwards designed a work that includes circles, arcs, and squares joined by a vertical chain. For Edwards, the work suggests a strong, united community that is hopeful for the future development of their neighborhood, a part of Charlottesville that has not commissioned public art for almost a century. Having retired in 2002 after 30 years of teaching at Rutgers University, Edwards travels widely and has the energy and determination to make a difference. His work is exhibited in galleries in Paris and London, as well as in Africa. He sees his current work as emerging not only from architectural concerns, but also from the mural paintings that he created in Harlem with the Smokehouse group. Art can actually “change places,” he realized. Edwards’s 21st-century sculptures are indicative of the evolution of his style and his resolve to leave his mark on the urbanscape. Adhering to the Modernist tradition, he believes that abstract art can reach and transform a large public.

Notes

1 My sincere thanks to Melvin Edwards for his insights into his work. Unless otherwise indicated, all quotations from Edwards are taken from an interview with the author on November 19, 2015.

2 Quoted by Catherine Craft in Melvin Edwards, Five Decades (Dallas: Nasher Sculpture Center, 2015), p. 18; originally published in Kellie Jones, “Interview with David Hammons” (1986), in Eye/Minded: Living and Writing Contemporary Art (Duke University Press, 2006), p. 249.

3 Quoted by Lowery Stokes Sims, “Melvin Edwards: An Artist’s Life and Philosophy,” in Melvin Edwards, Sculpture (Neuberger Museum of Art, 1993), p. 9.

4 Melvin Edwards, “Lynch Fragments,” Free Spirits: Annals of the Insurgent Imagination (1982), p. 96.

5 Interview with Michael Brenson, Bomb Magazine, November 2014.

6 Ibid.

...

Download original print version: