South South

Alexander Gray Associates, Germantown presents South South, an exhibition that examines poetics of space and orientation in works by five Gallery artists: Ricardo Brey, Luis Camnitzer, Melvin Edwards, Regina Silveira, and Valeska Soares. Even as movement across the globe remains constrained, these artists illuminate the imaginative potential of artworks to recontextualize travel, communication, and relation. The works, in a range of mediums, are also presented in a digital exhibition for South South Veza, an online community, anthology, live resource and aggregator dedicated to art from the Global South and its diaspora.

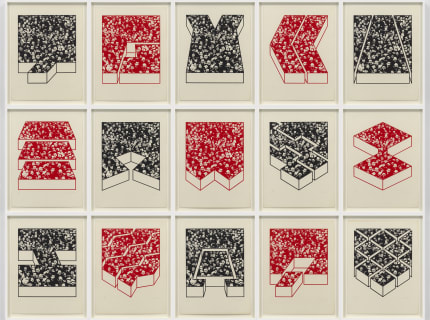

Luis Camnitzer’s Compass (2021) is a deceptively ordinary object, crucially adjusted. An old-fashioned compass has its traditional face replaced so that wherever it lands, the needle now points to only one cardinal direction: South. With his signature economy of gesture, Camnitzer invites the viewer to reconsider their own position and consequently how they view places and people in relation to themselves. Untitled (1968) is an elegant riff on the tenuous nature of individual perspective. The stenciled word “sun” descends from left to right until a horizon line, stops the letters short. If the text seems to have a clear meaning, the structure of the image subverts it: While most English speakers would read the text from left to right, reading it from right to left (as one would with some non-English alphabets) gives the graphic impression of a sunrise. Where Untitled makes deft use of horizontal space to illustrate this thought, Signature (1980) uses the sphere to give shape to the concept that universal scope and personal experience are simultaneously opposed and inseparable. Appropriating a globe as a Duchampian readymade, with Camnitzer’s signature scrawled across its circumference, yields another instance of shifting perspective. Signature can be seen as either reducing the world to the scope of the artist’s vision or expanding an individual artistic capacity to encompass the whole globe. The ambiguous meaning places the viewer in an interpretive dialogue with the work, which remains open to either––or neither––reading.

Where Camnitzer’s works place the poetics of time and space on a universal scale, Regina Silveira’s Touch #11 (2013) magnifies subjective, embodied experience. Six square aluminum prints depict silhouetted hands, a motif in Silveira’s work since the 1980s. The tender, personal prints are set against the aluminum in an oversized scale. This distortion in dimension––in this case of such a recognizable, individuated part of the body––creates an effect of both intimacy and mystery, what Silveira calls “gaps in perception.” These moments of simultaneous dissonance and recognition evoke in the viewer a reconsideration of scale, position, and perspective, illuminating the spaces of darkness in our perception and self-knowledge.

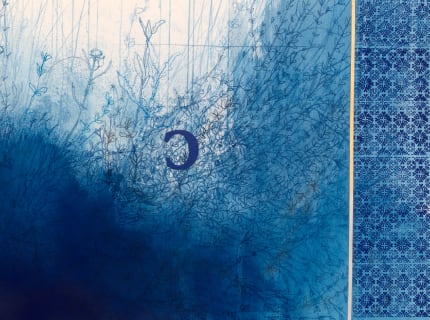

These poetics of space and orientation contain an intrinsic tension: How to reconcile, within a single artwork, the multiple valences of place and history that we all live, sometimes simultaneously? In Ricardo Brey’s work of the past decade, his meticulous approach reveals the subtle consonances across seemingly disparate narratives, languages, and aesthetics, which Brey transforms into cohesive objects of deep resonance. In Wooden Face (2013), he alludes to the colloquial Cuban idiom “cara de madera,” usually used in jest to refer to someone with a stoic “poker face.” An antique wooden ironing board supports a small rock with a trumpet protruding from it, circled by concentric strands of chaquira beads. Found black scarves meant to simulate hair around the face frame the sculpture, referencing traditional Fang masks from Cameroon and Gabon. In Fern at the edge of the road, a thistle plant drawn in bloodred chalk anchors the center of the composition. Its leaves and branches extend outwards towards the paper’s edges, underscoring the plant’s resilience. Gestural gouache brushstrokes and Baroque-inspired patterns center the focal point of the drawing, highlighting the growth of the thistle––essentially a weed that grows on the side of the road. Spawning roots and surviving distress, the thistle plant is a recurring motif in Brey’s practice, indicative of the artist’s own struggles and trajectory from Cuba to Belgium.

Brey’s journeys recall legacies of colonialism and the transatlantic slave trade, which are indelibly inscribed in the histories of his native Cuba and his current home of Belgium. It is a concern he shares with Melvin Edwards, whose decades-long Lynch Fragments series grapples evocatively with the experiences of the African diaspora in the United States. Luanda (1999) is one of the many Lynch Fragments focused on Edwards’ relationship with Africa, which has been significant in his work since his first visit to the continent at the height of the independence movements in the 1970s, to the establishment of his studio in Dakar, Senegal, which he has maintained since 2000. Luanda marks the artist’s visit to Angola in 1999, and pays tribute to the artists, intellectuals, and friends with whom he connected there. Straddling both Africa and the African Diaspora, the Lynch Fragments are an embodiment of inseparable histories.

These engagements across time and space are thrown into stark relief at our current point in history, which is so defined by immobility and marked by the presence of mortality. Throughout her career, Valeska Soares has described the complexities of a Brazilian identity whose fluidity can be uncomfortable: Feeling insufficiently Brazilian in her native country, while experiencing a foreigner’s alienation abroad, she occupies a space as a citizen of the world that can feel both cosmopolitan and adrift. This duality between global and individual frequently emerges in her work via a focus on the body, often initially concealed behind refined conceptualist strategies. Soares’s collage series Sugar Blues, begun in 2013, exemplifies this combination of vulnerable human emotions with rigorous formal composition. Made from the wrappers and boxes of sweets Soares has consumed, each piece in Sugar Blues can only exist because she has consumed more, weaving intense feelings of memory, pleasure, and longing into precise visual compositions. The empty wrappers also evoke a sense of melancholy and mortality, as residual markers of a tender interior body that no longer exists. The Sugar Blues works are meditations on the passage of time marked through consumption; their emotional poignancy and conceptual resonance take on a new poignancy in our present context, where time can seem to pass unmoored and unmarked.

Spanning mediums, continents, and languages, with concerns both collective and deeply personal, South South offers multiple points of entry for reconsidering our sense of perspective and our global position.