Luis Camnitzer: The Mediocrity of Beauty

Alexander Gray Associates presented an exhibition of artwork by Luis Camnitzer, featuring works in a variety of media dating from 1968 to the present. An accompanying catalogue was published in both English and Spanish, featuring the artist’s essay The Mediocrity of Beauty (2010).

The artworks on view conveyed Camnitzer’s skepticism of universal beauty, specifically symmetry as a defining visual characteristic of beauty. In the video Jane Doe (2012), Camnitzer fused fifty photographs of women’s faces—taken from online police reports, legal documents, and newspaper articles—utilizing image morphing software. The portrait of Jane Doe, a seemingly “beautiful” symmetrical face, resulted from the averaging out of individual features. The video shows a fictional face and story that provides an identity for Jane Doe. In the realm of the political, for his most recent suite of seven etchings, Symmetrical Jails (2014), Camnitzer stacked and mirrored each letter in the word “symmetry”—using the United Nations official languages Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian, Spanish, plus he adds German— to create seven unique characters. For the artist, “Words are never able to fully convey what one truly thinks: thoughts and feelings are pressed into an alien format, like when poetry tries to imprison poetics in stiltedness. Symmetry worsens this by curtailing the freedom of information.”

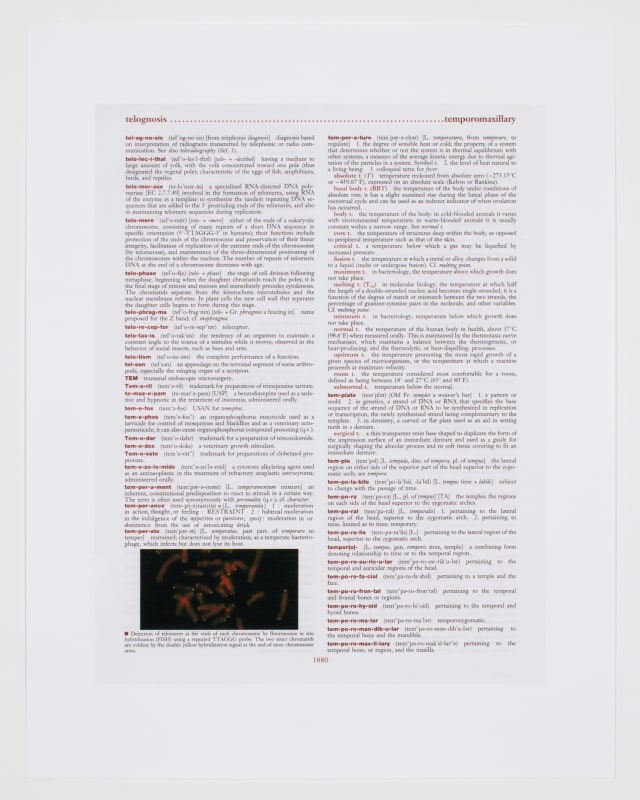

Camnitzer believes that art’s function is not to reinforce traditional notions of beauty, but rather, it can create alternative orders and frameworks, enabling an expanded perspective. This philosophy is represented in works such as Questions and Answers (1981), a series of ten photographs of ordinary objects, which the artist made under hypnosis; and Seven Virtues (2014), a seven-part graphic work in which Camnitzer indexed the seven cardinal and theological virtues—charity, courage, faith, fortitude, hope, temperance, prudence—into the pages of Dorland’s Medical Dictionary. Altering the clinical tone of this volume, he defined each virtue in the context of medical descriptions of ailments, which suggests a more nuanced understanding of the human state and the present condition of religious and scientific ethics.

Transgression has characterized Camnitzer’s practice since the mid-1960s, when he co-founded The New York Graphic Workshop with fellow artists Argentine Liliana Porter and Venezuelan José Guillermo Castillo (1939–1999). The etchings Self-portrait (1968–72), a series of five self-portraits that only include the inscription of the artist’s name and the date of creation, demonstrate this defining quality and question authorship, authenticity and seriality. Camnitzer’s interest in language extends to Please Look Away (2014), a room-size installation that invited the audience to walk into the immersive cage-like environment made of imperative inscriptions, such as “Please look away, you are invading my territory,” printed in white lettering on black vinyl banners adhered along the walls and floor of the Gallery, demarcating the alienation of physical space.

Situating elegance in the context of beauty, Camnitzer argues that simplicity is perhaps the most profound form of beauty. In 1973, Camnitzer created a series of drawings to document ephemeral installations he did between 1969 and 1972. The primary component in the installations had been succinct sentences describing objects or situations, paired with simple geometric shapes that stood as the corresponding illustration to the text. Works such as the drawing Aquí yace una obra de arte (1973), created after a 1972 installation of the same name, depicts a rectangular slab that serves as a tombstone with the inscription “Here Lies an Artwork;” a handwritten notation legible on the drawing’s margin provides installation instructions for how to exhibit the work as a three dimensional object. The invisibility of the artwork that lies under the tombstone speaks to Camnitzer’s pairing of direct images and text to encourage the viewer to generate alternative meanings. Camnitzer states, “I am interested in art as a formulation of and solution to problems, and it’s there where elegance is really important. In art, there may be many correct solutions, but the best is the most elegant among the correct ones. Elegance is not necessarily simple, but it is the one that may achieve the greatest complexity without getting lost in stupidity.”