Ricardo Brey: Doble Existencia / Double Existence

Alexander Gray Associates presented its first exhibition of work by Ricardo Brey (b. 1955), Doble Existencia / Double Existence. Born in Havana, Cuba, Brey has lived and worked in Ghent, Belgium since 1990. From the late 1970s onwards, Brey’s practice, which spans drawing, sculpture, and installation, has focused on his research into the origins of humankind’s co-existence in the world. The presentation features a selection of recent work encompassing the artist’s ongoing exploration of philosophical concepts like time, mythology, human expression, and the natural universe.

A child of the Cuban Revolution, Brey first received widespread critical attention in 1981 following his involvement with and inclusion in the landmark exhibition Volumen I at the Centro de Arte Internacional in Havana, contributing to a dynamic, experimental artistic scene in Cuba. Through the 1980s, Brey continued to mine Afro-Cuban traditions and colonialism’s legacy throughout Latin America. In 1992, at the invitation of Belgian curator Jan Hoet, Brey participated in Documenta IX with a monumental installation consisting of readymades and other salvaged objects that invoked a hybrid, transcultural mythology. Brey’s interest in harnessing the associative potential of found objects continued throughout the 1990s and informs his practice today. Since the early 2000s, the artist’s interest in the natural world has catalyzed projects like Universe (2002–2003), consisting of over 1,000 drawings illustrating an “entire” universe—including many species of fish, birds, insects, and plants—its ongoing supplement Annex (2003–2016), and Every Life is a Fire (2009–2015), a series of intricate boxes that unfold to reveal artistic microcosms of the observable world, which were included in the 2015 Venice Biennale, All the World’s Futures, curated by Okwui Enwezor.

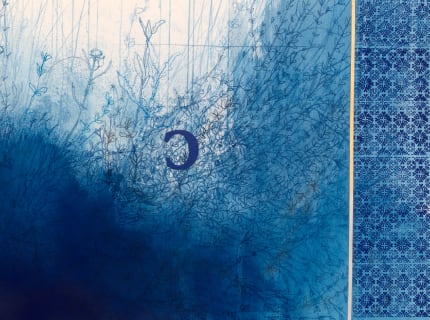

In his recent work, Brey continues investigating seemingly oppositional aspects of the human experience––the inherent tensions between binary concepts like life and death, dreams and nightmares, masculinity and femininity, black and white, manmade and organic––signaling an ongoing condition for the artist: what he refers to as “a double existence.” Borrowing the term from Swedish playwright August Strindberg, the phrase reflects competing yet complementary threads of consciousness that inform Brey’s artistic practice as hybrid and rhizomatic. Recent large-format drawings from Brey’s Inferno series like Stormclouds (2017) and Roots (2017) encapsulate the melancholy embedded in this dualism, as well as new sculptural works like Leo (2018) and Meditatie (2018), that reference both Flemish architecture and Yoruba spirituality.

Anchoring the exhibition was Rose of Jericho (2013–14) from Brey’s series Every Life is a Fire, underscoring the artist’s poignant reflection on the ephemeral. Inviting performative engagement by unclasping the four walls of the box and unfolding them to reveal a complex web of symbols, Brey’s boxes utilize enclosure to relish in surprise and wonder, representing the vast unknowable intricacies of the human mind. In Rose of Jericho, a mysterious black archival box opens and unfurls to reveal a small, wilted flower protected by a glass dome. Each wall of the box, lined with delicate paper bearing ornamental Baroque-inspired patterns, becomes a platform for the display of elements like frayed strands of rope and an accordion-style booklet, which includes original drawings incorporating the artist’s own handwriting and glistening silver pigment. At the box’s central axis, above a nest of cardboard, sits the rose of Jericho, informally known as the “resurrection plant” for its ability to survive after prolonged periods of drought. During arid climate seasons, the plant’s branches curve inward in a protective gesture, however, when exposed to small amounts of water, awaken from dormancy and flourish, in some cases even blossoming small flowers. A tender meditation on the cyclical nature of time as well as the resiliency of the Earth and the human spirit, Rose of Jericho metaphorically embodies the artist’s practice. As Brey states, “The box is our head, the box is our cave, the box is the attic, the box is the memory and the world. The boxes are an attempt to spatially represent… a hermeneutics of the soul to create a topography of the mind.”