-

Kamrooz Aram

-

Chloë Bass

-

Ricardo Brey

-

Teresa Burga

-

Luis Camnitzer

-

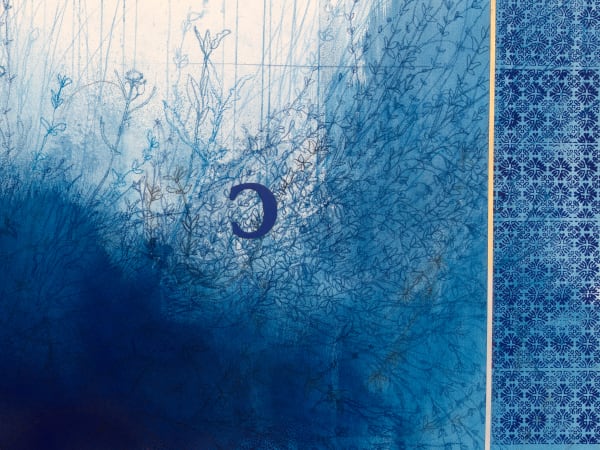

Bethany Collins

-

Melvin Edwards

-

Harmony Hammond

-

Jennie C. Jones

-

Kang Seung Lee

-

Steve Locke

-

Donald Moffett

-

Carrie Moyer

-

Betty Parsons

-

Ronny Quevedo

-

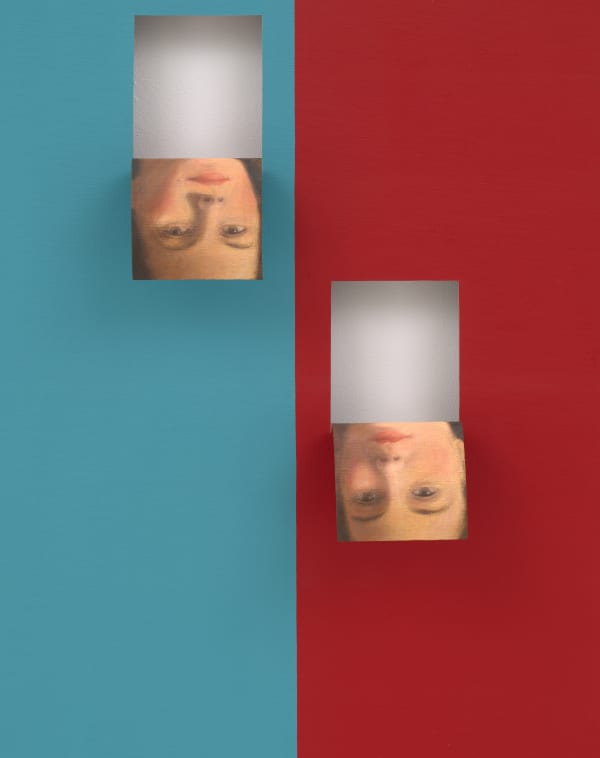

Joan Semmel

-

Hassan Sharif

-

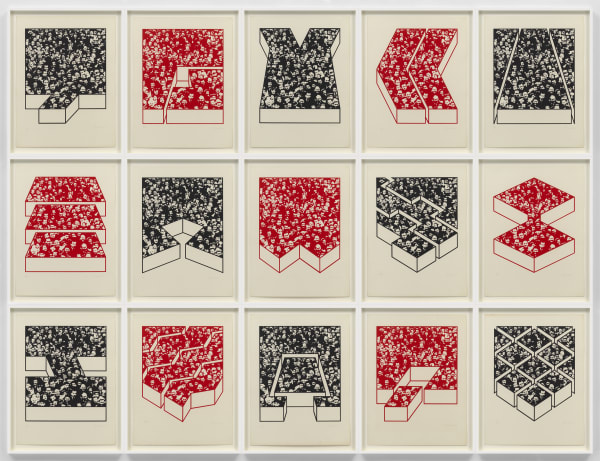

Regina Silveira

-

Valeska Soares

-

Hugh Steers

-

Ruby Sky Stiler

-

Dyani White Hawk