Art Basel 2022

Galleries Sector | Booth N20 (Hall 2.1) | Messeplatz 10, 4058 Basel, Switzerland | June 14–19, 2022

Preview (invitation-only): June 14–15, 2022

Public Days: June 16–19, 2022

Alexander Gray Associates presented recent and historical works by Frank Bowling, Ricardo Brey, Luis Camnitzer, Harmony Hammond, Jennie C. Jones, Steve Locke, Betty Parsons, Ronny Quevedo, Joan Semmel, Valeska Soares, Hugh Steers, and Jack Whitten. Featuring a range of abstract and figurative paintings, sculptures, and works on paper, the Gallery’s presentation highlights these artists’ commitment to artistic innovation through works that break new conceptual, formal, and material ground.

For decades, Frank Bowling and Jack Whitten explored the formal possibilities and material potentialities of painting. Together, their groundbreaking approaches to abstraction left an indelible mark on contemporary art history. Pioneering alternative methods of paint application, Bowling crafts paintings that feature mesmeric chromatic effects. Works like Serpent Drape (2013) boast heavily worked surfaces, complete with topographical accumulations of gel medium that recall the craggy surfaces of the artist’s earlier 1980s foam reliefs. Meanwhile, Whitten reimagined painting to map geographic, social, and psychological locations that reflected on the African American experience. Whitten’s Single Loop: For Toots (2012) belongs to series of late paintings by the artist that feature loop imagery and investigate the relationship between figure and ground. Titled in homage to the artist’s sister, Toots, the work recalls the artist’s 1970s experiments with Xerox toner and his gestural Slab Paintings and Greek Alphabet canvases of the same decade.

Like Whitten, Betty Parsons explored the link between lived experience and artistic innovation. Parsons’s unique mode of abstraction employed her intuitive approach to color and form to capture feelings and impressions of places and experiences. Juxtaposing sinuous curvilinear forms against static biomorphic masses, works like No Squares (1970) vibrate with a playful dynamism that embodies the “sheer energy” that Parsons strove to translate through her art. In contrast to Parsons’s evocative approach to abstraction, Hugh Steers remained committed to figuration throughout his career—cut tragically short by AIDS at just 32. In works like Blue Dress (1992) he paints a man in high heels trying on a blue dress in front of a mirror. The intimate scene underscores the artist’s assertion that “vulnerability can be a source of power.”

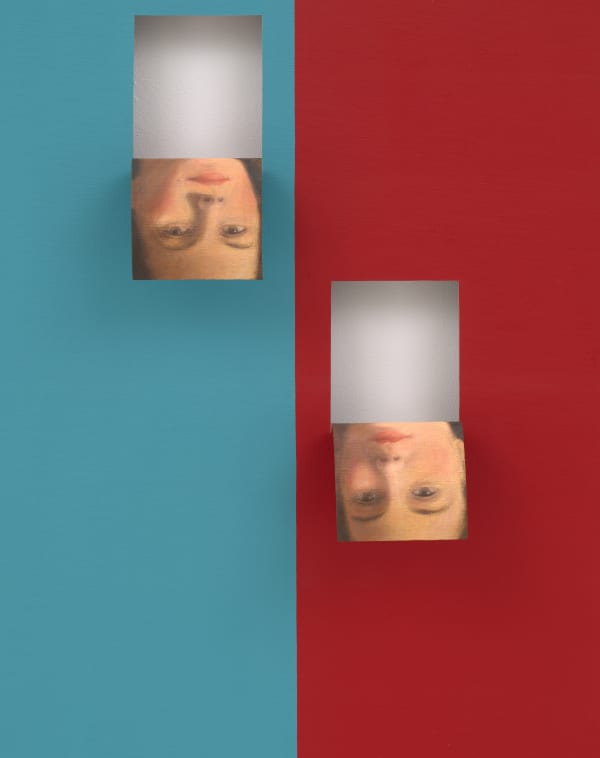

Like Steers, Steve Locke’s paintings also investigate themes of male desire and vulnerability. Critically engaging with the legacy of portraiture in the Western canon, works like the coward, 2010–2012 (2010) feature a man’s head with his tongue hanging out of his mouth. Simultaneously comical, sensual, and disturbing, this gesture subverts traditional configurations of masculinity and power. Further exploring the reclamatory power of figuration, Joan Semmel’s Overlays (1992–96) like Bottoms Up (1973/1992) firmly assert the sexuality of older women while challenging the notion of an idealized female body.

In contrast, Harmony Hammond and Ronny Quevedo use material-driven approaches to abstraction to center historically excluded and undervalued communities and artisan traditions. In Chenille #9 (2019), Hammond visually references the needlework of chenille textile work using thick layers of oil paint and Dorland’s wax that mimic human skin. Similarly, Quevedo’s myself when I am real – sin ti soy nadie (2021) uses material and subject matter relating to his mother’s profession as a seamstress to create a dynamic abstract composition. Adopting a metaphysical approach to material engagement, Ricardo Brey draws upon his Afro-Cuban spiritual heritage in his practice, specifically the belief that using abandoned or neglected objects can renew them and give them new life. In Weaving Hope (2017), Brey drapes a beaded net of faux jet over a found black globe, symbolically casting a protective lattice—and shroud—over the planet.

Meanwhile, Jennie C. Jones’s recent minimalist paintings seamlessly integrate visual practices with aural ones. Works like Gray Pitchless Measure, Black Edge (2021) directly reference musical terminologies both in their titles and compositions. Frequently incorporating sound dampening materials into their compositions, Jones’s paintings encourage an awareness, even anticipation, of sound. “I always say they’re active even when there’s no sound in the room,” she explains. “They are affecting the subtlest of sounds in the space—dampening and absorbing even the human voice.”

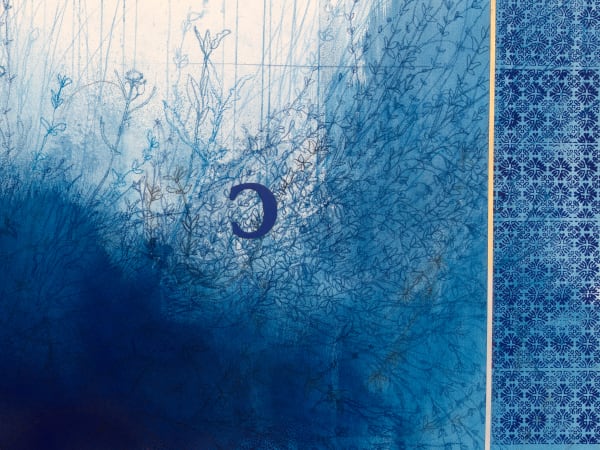

Similarly evocative, Luis Camnitzer’s artworks from the 1970s present viewers with ambiguous relationships between images and text. Illustrative of Camnitzer’s interest in explicitly linking objects and words, works like John and Lillian (1974), part of the artist’s series of Object Boxes (1971–80), invite viewers to construct relationships between inscrutable figurative elements and phrases. Echoing this open-endedness, Valeska Soares rejects the necessity of monolithic narrative, opting instead to provide people with what she terms “triggers that activate memories and contexts.” In Doubleface (Artic Blue) (2018), Soares collapses the disparate histories of art and objects by transforming a recovered vintage oil painting into a monochromatic contemporary work, whose surface uncurls to reveal hidden figural elements.

Together, these twelve artists use their practices to reimagine the limits of their respective mediums, defining new paradigms through their varied approaches to abstraction, materiality, and representation. Pushing beyond reductive frameworks and antiquated norms, they exemplify Camnitzer’s assertion that the true power of art resides in its ability to give us “a glimpse not only of something we do not know, but of something that—at least for a moment—is unknowable.”