Frieze London (Online)

Preview (invitation-only): October 7 - 8, 2020

Public days: October 9 - 16, 2020

Digital Event: Virtual In-conversation 'Gallery as Practice' hosted by Gallery Director Nichole Caruso with panelists Michelle Grabner (The Suburban, Milwaukee, WI), Davida Nemeroff (Night Gallery, Los Angeles), Eric Veit (Bodega, New York), and Rachel Vorsanger (Collection and Research Manager, Betty Parsons Foundation, New York).

Friday, October 9, 2020, 3 PM — 4 PM EST

View the event here.

Alexander Gray Associates presented a selection of recent and historic paintings, sculptures, and works on paper by nine Gallery artists, including Frank Bowling, Teresa Burga, Harmony Hammond, Lorraine O’Grady, Betty Parsons, Joan Semmel, Hassan Sharif, Valeska Soares, and Hugh Steers. Ranging from the abstract to the figurative, the Gallery’s display articulated the relationship between artistic gesture and the body while foregrounding innovative approaches to composition and content that break new visual and conceptual ground.

In recent 2020 paintings, Joan Semmel continues to expand understandings of nude self-portraiture. Her gestural use of paint in Curve (2020) recalls her engagement with Abstract Expressionism in the 1960s while the canvas’ bright color marks a return to the artist’s 1970s palette of vivid, highly saturated tones. A departure from Semmel’s figuration, Betty Parsons’ abstract canvas Miami I (1966) takes its inspiration from the artist’s physical travels. Isolating elements of Parsons’ experience in the city of Miami, the composition boasts a rhythmic arrangement of triangular shapes against a shadowy green ground. Similarly evocative, Frank Bowling’s Head (2013) suggests the rough contours of a profile. The painting features ripples of acrylic that recall the flow of water—the constant tug of oceanic currents. Reflective of the artist’s own journeys as he crisscrossed the Atlantic and moved from Guyana to London and New York, the work imbues abstraction with personal narrative.

Like Bowling, Harmony Hammond crafts paintings that bring content into the realm of abstraction. In Chenille #2 (2016–2017), the artist layers panels of rough burlap onto canvas. Coating the fabric in thick layers of paint—building the surface up until it suggests a near bodily presence—Hammond evokes, in the words of the art historian Tirza True Latimer, “… not unity and purity—but the piecing together … associated with traditionally feminine creative acts.” Also piecing together disparate materials into a cohesive whole, Hassan Sharif’s Cotton Rope 8 (2012) weaves together rope and wire. Before his death in 2016, the artist imbued the work’s creation with a tacit sensuality, relating the finished sculpture and its materials to an eroticized body. Further suffusing its making with corporeality, he once noted that in order to weave it he had to “… use sharp tools [such as] scissors. Scissors have to do with the cutting hair, cutting nails; scissors to do with the body …”

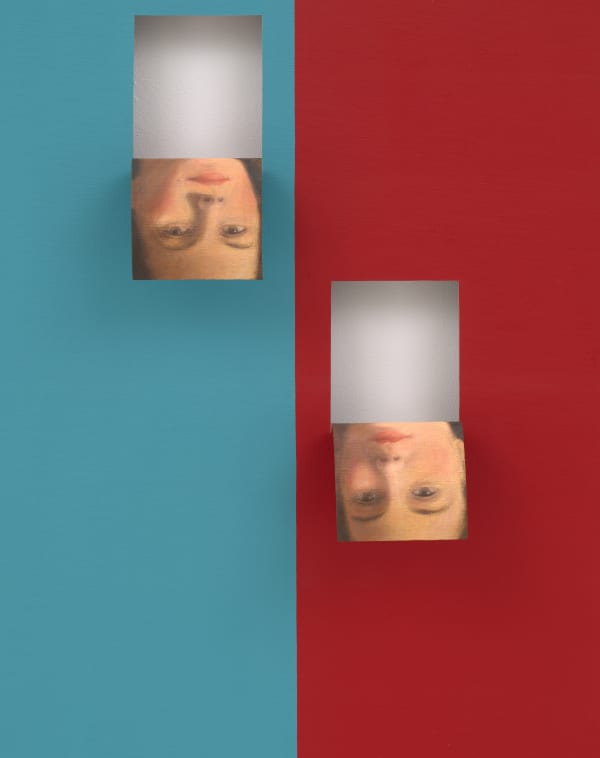

In contrast to Hammond and Sharif’s material-driven approach, Hugh Steers’ figurative paintings record the realities of life under the specter of AIDS. Capturing the emotional and political tenor of New York in the late 1980s and 1990s, works like Two Chairs (1993) update the domestic scenes of Post-Impressionists like Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard, charging them with an unsettling psychological drama. Painted two years before the artist’s death in 1995 from AIDS-related complications, this ambiguous image touches on themes of isolation, illness, and sexuality. Like Steers’ poignant composition, Lorraine O’Grady’s Miscegenated Family Album (1980/1994) also marries the art historical with the contemporary. Pairing ancient images of sculptures and reliefs of Nefertiti and her relations with personal photographs of the artist and her family, O’Grady draws parallels between the two families, presenting both as products of shared forces of migration and hybridization.

While O’Grady’s diptychs map a personal history entangled with empire and enslavement, Teresa Burga’s Insomnia Drawings (1970s—2000s) construct a different type of cartography. Inwardly focused compositions that chart the artist’s sleep-deprived psychological state, these automatic drawings consist of hypnotic lines and geometric patterns that create the disorienting sensation of an optical illusion. Also referencing the subconscious—forgotten memories and obscured histories—Valeska Soares’ Palimpsest I (2016) presents a series of Brazilian boxes installed so that they share a horizon line. Through this gesture, Soares constructs a palimpsest that subsumes each box’s singular identity, its maker, owner, and the objects it once held. Suggesting the only constant in life is the horizon, which levels all eras, civilizations, and geographies, the installation muses on life’s inevitability.

As Bowling once argued about his paintings, “I don’t think what you see or feel in the world when you open your eyes for the first time ever leaves you. … Historical memory is hardly ever erased,” so too do the artists in the Gallery’s presentation visually articulate these memories. Their artworks, tributes to lived experiences—moments of introspection, exultation, and trauma—marry gesture with content until paint becomes an ocean and ancient sculptures become family.