Frieze Los Angeles

February 13 – 16, 2020

Booth A7

Paramount Pictures Studio

Los Angeles, CA

Alexander Gray Associates presented recent and historical works by Ricardo Brey, Frank Bowling, Luis Camnitzer, Melvin Edwards, Harmony Hammond, Betty Parsons, Joan Semmel, Valeska Soares, Hugh Steers, and Jack Whitten. Featuring a range of abstract and figurative works, the Gallery’s display foregrounds these artists’ commitment to challenging conceptual, formal, and sociopolitical conventions.

Ricardo Brey’s ongoing project, Every Life is a Fire (2009–Present) anchors the gallery's presentation. Consisting of a series of boxes that unfold to reveal miniature worlds of sculptural assemblages and inviting performative engagement, the archival boxes unfurl as they are opened—host to a complex web of symbols. Juxtaposing enclosure with expansiveness, each work’s unveiling inspires surprise and wonder while representing the vast unknowable intricacies of the human mind. Every Life is a Fire celebrates interiority and welcomes multiple interpretations drawn from Brey’s own cross-cultural references. In The Uncanny (2015), a neoclassical bust anchors the box and is positioned to stare at its own reflection in a small mirror, evoking the myth of Narcissus. In contrast, Seven Roses (2012), which features rosebuds made of scrap metal as the box’s central axis, is dedicated to the Afro-Cuban deity Yemayá, who is honored in Santería as the goddess of the sea and the mother of all children on Earth. Incorporating found fleetwood, Driftwood and Pebbles (2014) suggests the ephemerality of time itself, the transient nature of youth-like innocence, and the influence of the moon on oceanic tides.

About the series’ symbolic potential, Brey states, “What fascinates me is the origin of the human race, our culture and our society. It is from the relationship between different life forms and between the communities of earlier and today that we can deduce the state of the present world. We can learn from our evolutionary past and thus consider our current condition critically. From a global approach man can emphasize the underlying connection between everything around us.”

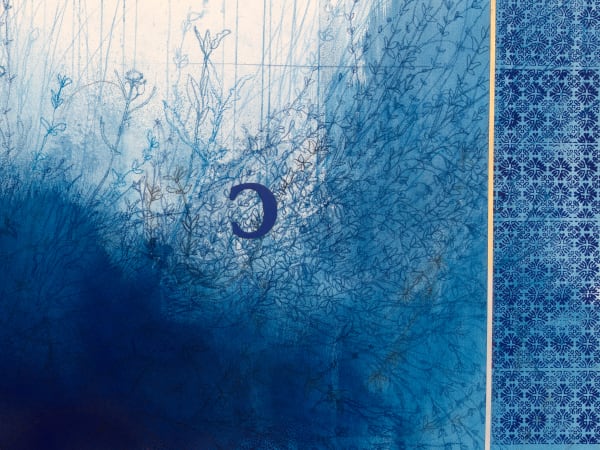

Since the 1960s, Frank Bowling’s practice has been defined by its integration of autobiography and postcolonial geopolitics into abstraction. His singular approach to painting expands upon the legacy of the New York School while reinterpreting and updating the landscape tradition of English masters like JMW Turner. Ultimately committed to foregrounding materials and process, Bowling utilizes multiple innovative techniques—dripping, staining, collaging, sewing, etc.—to create dynamic and evocative compositions.

Since the 1960s, Luis Camnitzer has developed a body of work that explores language as a primary medium. In Utopiary (2010), Camnitzer explores written language and its ability to generate meaning beyond the physical object. A small brass plaque with the word “utopiary” serves as the only written text––a combination of the words “utopia” and “topiary.” Above the plaque, the work consists of red graph paper that has been shredded to reveal the underside of the paper, leaving behind the outline of a tree. Utilizing clever wordplay, Camnitzer suggests that topiaries, which symbolize humanity’s attempt to intervene and control nature, are just like false utopias.

Melvin Edwards’ sculptural practice capitalizes on the potential of salvaged industrial and agricultural elements to evoke competing narratives around labor, violence, and the African Diaspora. In On the Spot (1985) Edwards contrasts a blade with a chain. At once foregrounding the brutalism and oppression of slavery, these objects also reference family and African metalworking traditions.

Harmony Hammond’s recent paintings’ focus on materiality and the indexical derives from and remains in conversation with her feminist work of the 1970s. In Bandaged Grid #2 (2016), puncture holes demarcate the grid, at times obscured by the strips of found and recycled fabric that Hammond has added to the canvas. Through layers of material—both fiber and paint—she creates a work that lies between object and painting; the collage of fabric pieces and varying applications of paint suggest a field of lived experience embedded in the canvas.

Betty Parsons trained as a landscape painter, first turning to abstraction in the late 1940s. In Untitled (1956), Parsons brings an experimental approach to abstraction not tied to any single style. The vivid palette harnesses an expressive use of color applied in layers of gestural brushstrokes in a loose repetition of the canvas’s shape while the center is animated by forms in yellow and green that have been inscribed with the back of the artist’s brush.

Since the 1970s, Joan Semmel has centered her practice around representations of the body from a female perspective. In Taking Cover (2012), she employs her own body as subject in a meditation on flesh, using a range of tones to convey the body’s lines and curves in varying light and shadow. The handling of paint foregrounds gestural brushwork stemming back to her roots in Abstract Expressionism.

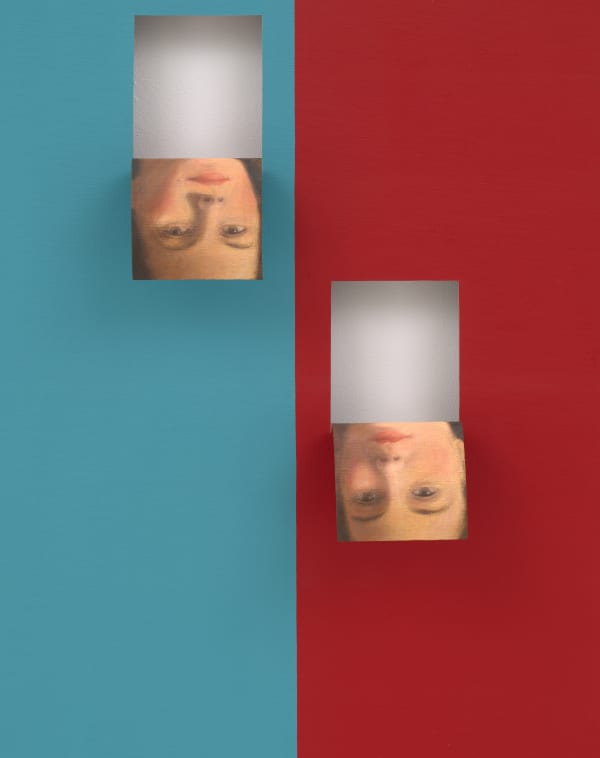

Utilizing tools of minimalism, Valeska Soares’ practice embraces emotion and humanity, mining territories of desire, loss, memory, and time. In Doubleface (Sepia/Permanent Violet Medium, Soft Mixing White) (2019), part of a series of Doubleface portraits, Soares transforms a vintage oil painting, evoking the allure and mystery triggered by covered images.

Hugh Steers embraced representation and figuration at a time when such approaches were especially unfashionable, capturing the emotional and political tenor of New York in the late 1980s and early 1990s as well as the impact of queer identity and the AIDS crisis. Cat Rub (1987) features two men and a black cat in a domestic setting, in an open-ended composition alluding to narratives around sexuality, companionship, and desire, and reflecting the artist's own struggles as a gay man in the time of AIDS.

Jack Whitten was a pioneer in abstract painting who challenged preconceived notions of what painting could be. Before his death in 2018, Whitten created a series of works that expanded on the collaged fields of his tessellated constructions of the last decade. A homage to one of the founding figures of abstract art, Ode to Kandinsky (2013) belongs to this body of late work. Deconstructing the mosaic-like tiles of earlier paintings and re-imagining them as ribbons and long lozenges of acrylic, the geometry of Ode recalls that of Kandinsky's compositions.

About Frieze Los Angeles

Frieze Los Angeles presents the best of Los Angeles and international contemporary art by emerging and established artists, alongside a curated program of talks, films and artists’ projects in the backlot movie set at Paramount.